Over almost 40 years, the Coen Brothers have become two of the most distinctive filmmakers in American cinema. From their indie debut Blood Simple to the Oscar-winning triumph of No Country For Old Men, they have carved out a singular niche in Hollywood, subverting the tropes of well-worn genres to surprise, delight, and confound our expectations at every turn.

Like other esteemed directors who have earned namesake adjectives, we can all probably recognise the Coenesque qualities of their movies by now. You have the dark humour, fine-honed dialogue, offbeat narratives, and memorable characters, all wrapped up in a pristine package. The Coens are fine filmmakers and have always worked with outstanding actors, cinematographers, and composers, all of whom contribute to the reassuring seam of quality running throughout their filmography.

The Coens also make movies that work on different levels. You can enjoy them purely for the cinematic buzz, but there are also deeper themes to mull over. Throughout their career, the siblings have been preoccupied with fate, choice, and the randomness of human existence, often entrusting the audience to pick through these ideas on their own. Let’s take a look at 20 classic scenes from their incredible body of work…

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs - The Gal Who Got Rattled

Anthology movies are always a mixed bag and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is no different. Returning to the Old West again after their earlier remake of True Grit, the stories here veer from amusing, such as Tim Blake Nelson’s eponymous singing gunslinger, to the downright tragic. “The Gal Who Got Rattled” is not only the most powerful vignette in the whole film, it also delivers one of the most devastating payoffs in any Coen Brothers movie.

Zoe Kazan plays Alice Longbaugh, who is left to fend for herself on a wagon train heading west after her domineering brother passes away. Over the course of the journey, she develops a relationship with Billy (Bill Heck), a rugged trail leader, who promises to marry her once they reach their destination. He tells his partner, Mr. Arthur (Grainger Hines), that this will be their last trip together as he plans to settle down.

Any prospects of happiness, however, are waylaid when Alice wanders away from the wagon train looking for her dog. Mr. Arthur goes to find her, but they spot a Native American war party approaching. Preparing for a fight, Mr. Arthur gives Alice a pistol and, knowing she will be abducted or worse if the warriors capture her, tells her to use it on herself if he is killed.

Mr. Arthur bravely fends off the war party but is caught unawares by one remaining warrior, who knocks him to the ground. For a moment, it appears that he has been killed, but he manages to shoot his assailant and return to Alice, only to find she took his advice and shot herself. Mr. Arthur returns to the wagon train faced with the prospect of breaking the news to Billy.

This story really stands out as the most authentically tragic moment in the entire Coen filmography. The Coens usually keep their distance when it comes to killing off their characters; most infamously, the protagonist in No Country For Old Men is dispatched off-screen, and even the death of Donnie in The Big Lebowski is given a comic payoff.

The death of Alice comes as a real sucker punch, and her unfortunate and needless death is made all the more resonant by Kazan’s wonderful performance. Alice goes from a meek girl following her brother’s lead to a strong young woman taking control of her situation, and the heart-breaking irony is that finding her agency ultimately leads her away from safety into mortal danger.

Alice’s story also stands out because, aside from Marge in Fargo, the Coens don’t write all that many memorable characters for women. Alice is certainly one of their best.

Barton Fink - Are You in Pictures?

One of the Coens’ most enigmatic endings comes at the conclusion of one of their most ambiguous films, Barton Fink, and it’s an ending that I often find myself pondering at odd moments during my day.

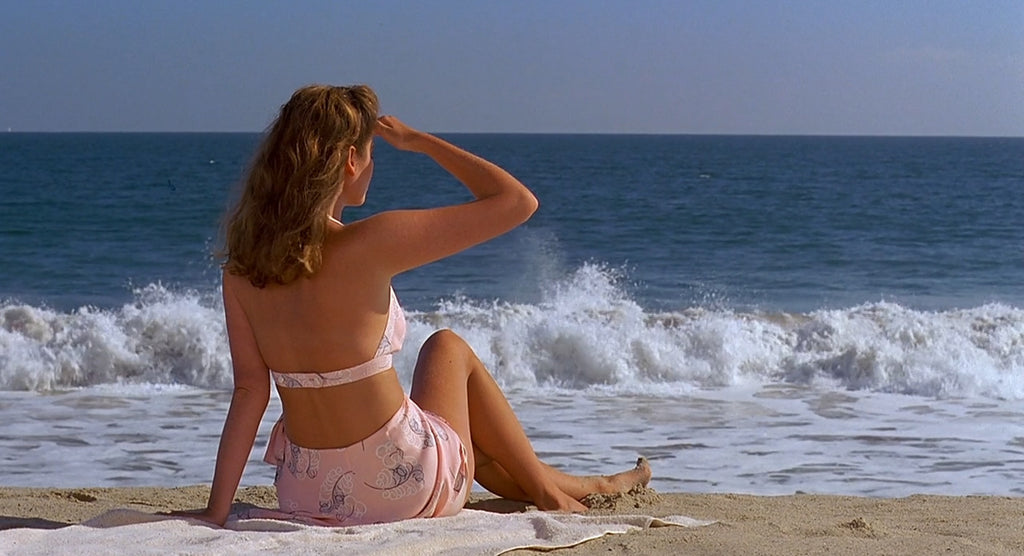

After Barton Fink (John Turturro) is thoroughly monstered by studio head Jack Lipnick (Michael Werner) for his pretentious wrestling screenplay, the shellshocked writer wanders along a beautiful stretch of beach, carrying a box that may or may not contain a severed head.

He spots an attractive young woman approaching from the other direction and sits down on the sand. She briefly engages him in small talk, sitting down in front of him. As the chat runs dry, Barton comments on her beauty and asks if she’s in pictures. She coyly tells him not to be silly and turns away to look at the ocean.

That’s when we, and Barton, recognise the scene. The way the woman is posed, gazing out to sea, exactly matches the picture above his desk in the Hotel Earle, an image he has been looking at all movie as he battled writer’s block.

What does it mean? The Coens leave that up to us. Barton has been struggling to bring a work of art that he considers beneath him to life. When he finally manages to complete it, Lipnick’s reaction effectively ends his career. Now he is free from “the life of the mind”, and the bright, airy beach setting contrasts with the claustrophobic hotel where most of the movie is set. Now he sees another example of cheap art, the picture of the woman on the beach, magically come to life before his eyes. It’s easy when you don’t overthink it.

Fargo - Two More Months

Some may quote the grisly woodchipper scene, but the best moment in Fargo comes after that. After heavily pregnant police chief Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand) has bravely apprehended silent killer Gaear Grimsrud (Peter Stomare) and solved the kidnapping case, she settles down for bed with her husband Norm (John Carroll Lynch). She congratulates him on getting one of his paintings accepted for the new three-cent-stamp, then they cuddle up and think ahead to their new baby. “Two more months.”

It’s a quiet and uncharacteristically tender scene for the Coens, a loving moment between a happily married couple. After a grubby kidnapping plot driven by desperation and greed, it acknowledges that although terrible things happen in the world, there is still plenty of room for love and hope for the future.

It’s an optimistic note, with the same thread of humanism that runs through the movie and finds its form in Marge. Building the film around a warm three-dimensional character like her was a sign that the Coens were maturing as filmmakers and they were rewarded for it. Fargo was their biggest hit to that point and it received seven Oscar nominations including Best Picture and Best Director, and McDormand deservedly won Best Actress for her performance.

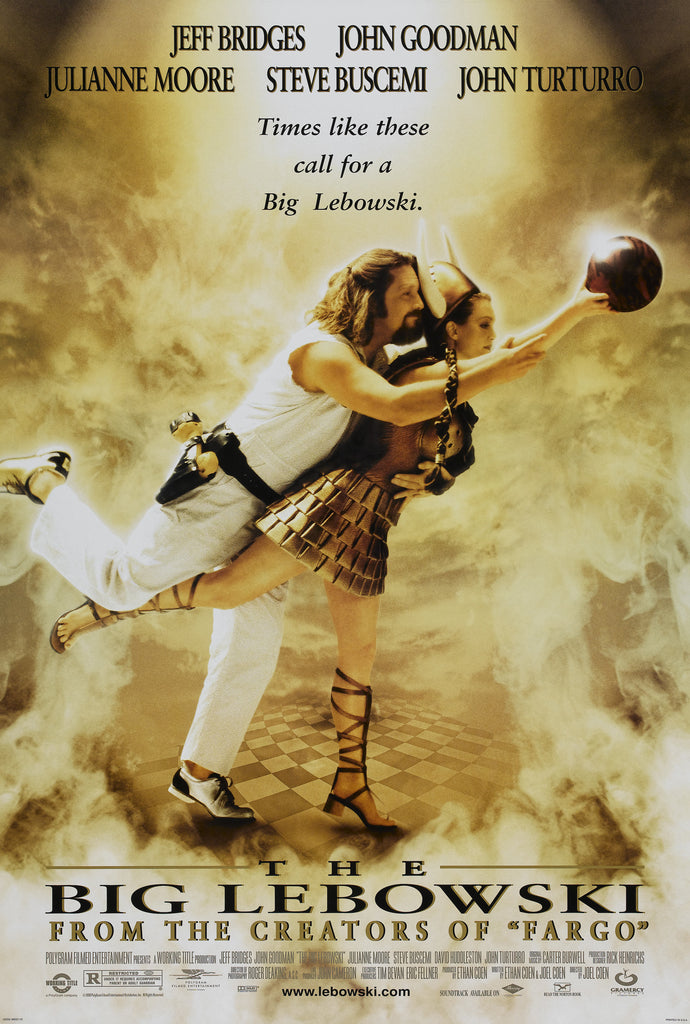

The Big Lebowski - Jesus Quintana

As a man of leisure, Jeff “The Dude” Lebowski (Jeff Bridges) spends his days driving around, smoking weed, drinking White Russians, having the occasional acid flashback, and bowling with his buddies Walter (John Goodman) and Donnie (Steve Buscemi). When he is hired as a bagman to hand over the ransom for a millionaire’s kidnapped wife, he uses the lanes as an ad-hoc meeting room too. That’s where we first meet Jesus Quintana (John Turturro).

The Coen Brothers are great at writing off-the-wall side characters, and few receive such a memorable entrance. Filmed in glorious slow motion to the brilliant Latino cover of “Hotel California” by the Gypsy Kings, we see Jesus in his fetching mauve bowling outfit tongue his ball and knock down a strike before launching into a preening celebratory dance.

He obviously thinks he’s some kind of superhero of the lanes, but we find out the truth from Walter: Jesus is a sex offender who got busted for exposing himself to kids. Jesus gives The Dude and the gang some big talk about “f**king them up” in their upcoming semi final match, leading to a line from the Dude that sums up his entire ethos: “Well, you know, that’s just like, your opinion, man.”

Jesus Quintana may be a total nonce who is only onscreen for about two minutes, but he has become a fan favourite and even starred in his own spinoff movie, The Jesus Rolls.

The Hudsucker Proxy - Norville’s Great Fall

The Hudsucker Proxy often gets a bad rap, but I’ll stick my neck out and say it is one of my favourite Coen Brothers movies. It’s so packed with energetic visual gags, breakneck wordplay, and it also features one of the most audacious endings ever.

After Norville Barnes (Tim Robbins) rises from lowly mail clerk to President of Hudsucker Industries thanks to his genius invention of the hula hoop (see: Part One), ruthless Vice President Sidney J. Mussberger (Paul Newman) plots to break his patsy and take control of the company. He engineers a scandal accusing Norville of stealing his next great innovation, a flexible straw (“Y’know, for drinks”) from Buzz (Jim True), the corporation’s hyperactive elevator operator.

Disgraced and pursued by an angry mob, Norville prepares to follow the previous President, Waring Hudsucker (Charles Durning) out of the 44th floor window to his death. He changes his mind at the last moment but slips and falls. As he plummets towards the street far below it looks like curtains…

But then, Norville freezes in mid-air. Moses (Bill Cobbs), the janitor in charge of maintaining the Hudsucker building’s enormous clock, has wedged a broom handle in its cogs, freezing time. Mussberger’s henchman Aloysius (Harry Bugin) has other ideas. As the two men fight, Norville receives a pep talk from his predecessor, who is now an angel sporting wings and a hula hoop halo.

Time is set into motion once again, continuing Norville’s fall. Just as he is about to splatter himself across the pavement, Moses freezes him again a few inches above the ground by jamming the clock with his opponent’s dentures. They give way, letting Norville complete his descent with a roll and a hoot of joy.

It’s a thrilling scene that thumbs its nose at reality, made all the more euphoric by Carter Burwell’s stirring rearrangement of Khachaturian’s “Adagio from Spartacus,” which swells in the background and crescendos just as Norville hits the ground and survives his improbable fall.

Blood Simple - Premature Burial

Texan bar owner Marty (Dan Hedaya) suspects his wife Abby (Frances McDormand) is having a fling with one of his employees, Ray (John Getz). To get some incriminating evidence, he hires sleazy private eye Visser (M. Emmet Walsh) to follow them around. The gumshoe isn’t content with the original fee, and a chain of events leads to him killing Marty and framing Abby for the murder. When Ray finds out what happened, he decides that he needs to clean up the mess and get rid of the body…

For the next 12 wordless, breathless minutes, we follow Ray as he drives Marty’s body out to the middle of nowhere to dispose of the corpse, only to realise that his old boss isn’t quite as dead as he thought. Joel Coen mercilessly cranks up the tension as Ray wavers on the best way to finish him off, almost getting caught by a passing lorry driver, before settling on the most callous method: Burying him alive.

It’s a turning point for Ray, going from immoral to just plain indefensible, but the Coens pull off the neat trick of putting us in his shoes. Like the scene in Psycho when Norman Bates is trying to dispose of Marion Crane’s car, we should want him to get caught but our heart stops when he almost comes unstuck. Blood Simple was a nerveless debut from the Brothers, and the bravura burial sequence really marked them as filmmakers to watch.

No Country For Old Men - The Coin Toss

No Country For Old Men gives us one of the Coen Brothers’ most memorable villains. Played with murderous intensity by Javier Bardem, hitman Anton Chigurrh is a relentless force of nature. After he is arrested by the hapless local law enforcement, he quickly makes his escape by throttling a deputy with his handcuffs before waylaying and killing a motorist.

Chigurrh stops off at an isolated gas station, leading to a chilling conversation with its Proprietor (Gene Jones). The old man makes the mistake of passing a little small talk, which prompts the assassin to embark on his own intimidating line of inquiry. The Proprietor instinctively knows he has overstepped some boundary, and Chigurrh decides to play a game of heads or tails without telling him what he stands to win or lose. Of course, having already seen Chigurrh cold-bloodedly kill the deputy and the motorist, we know a similar fate is potentially crushing in on the amiable old gent.

The tension is unbearable, made all the more believable due to the Coens’ decision to use no music, letting the pauses and deadly silences stretch out between the two men. Bardem is rightly celebrated for his dead-eyed performance as Chigurrh (for which he won the Oscar for Best Supporting Actor) but Jones also deserves credit for his part in the classic scene. The Proprietor knows he’s in danger from the moment the conversation turns, and Jones does a brilliant job of putting across the old man’s sense of nervousness, bafflement, and fear as the interaction escalates.

The Proprietor wins the toss and Chigurrh leaves him unharmed, telling him to keep the lucky quarter separate from the other loose change, otherwise “it’ll get mixed in with the others and become just a coin. Which it is.”

It is the film’s most famous scene and the clearest distillation of the Coen Brothers’ fascination with randomness, fate, and choice. Both men arrive at that crisis point due to the choices they have made throughout their life, and the rest of the Proprietor’s existence balances on the toss of a coin… which, as Chigurrh notes, has also travelled 22 years to play its part in the game.

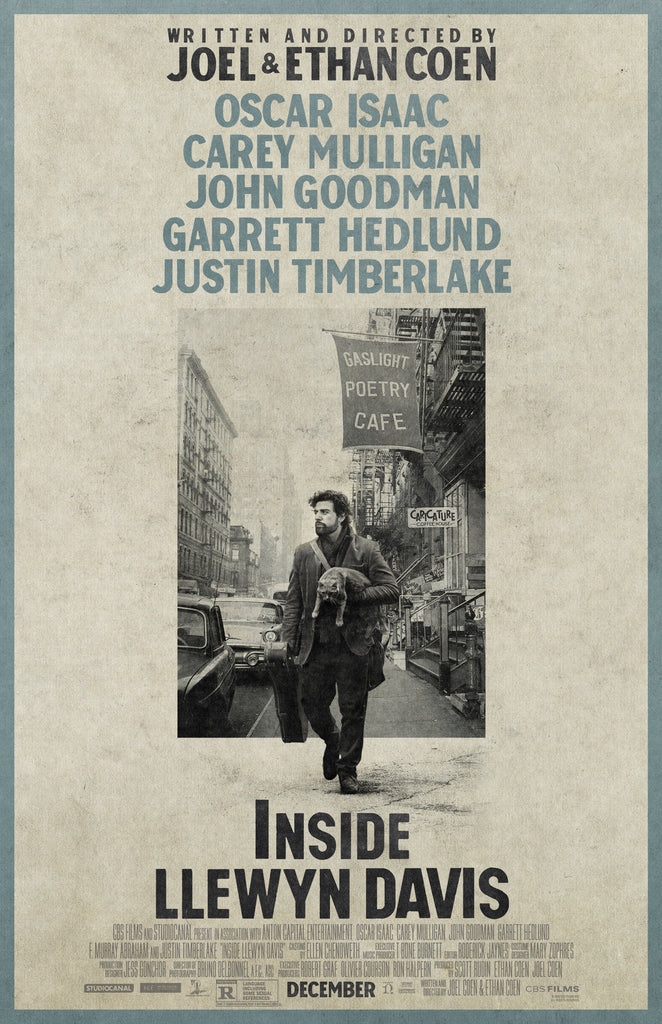

Inside Llewyn Davis - The Shoals of Herring

“The Shoals of Herring” was originally written by Ewan McColl for the award-winning 1960 BBC radio ballad Singing the Fishing, a collection of interviews with old-school fishermen working the seas off Britain’s east coast. The song was new but sounded like it had been around forever, a lusty sea shanty celebrating life and labour on the waves. Many of the subjects were from East Anglian ports and, having grown up in that part of the world, I love hearing the ballad for those old Suffolk and Norfolk accents.

I was delighted when the song cropped up so unexpectedly in Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coens’ melancholy snapshot of the life of a forlorn folk singer trying to catch a break in the emerging folk scene of New York in the early ‘60s.

Davis, played so brilliantly by Oscar Isaac (it was a crime that he didn’t receive an Oscar nomination), is not a great person. He’s selfish, irresponsible, cynical, and self-destructive. But boy, can he sing. When casting the part, the Coens opted for an actor who could sing rather than the other way around, and Isaac is perfect as the talented but unfocused singer.

Isaac’s performance of the beautifully curated folk songs is riveting, and “The Shoals of Herring” gives us a little insight into why Davis is such an asshole. When a promising audition in Chicago doesn’t go his way, Davis is about to throw it all in and signs up to work as a seaman instead, following in his father’s footsteps.

Before he departs, Davis goes to visit his elderly and infirm dad Hugh (Stan Carp) at a dreary old people’s home. Sitting in his armchair by the window, Hugh just glares at his boy with contempt. Davis breaks out the guitar and sings a song that his dad liked in the past, “The Shoals of Herring.”

As Davis sings, the expression on the old man’s face changes. He starts breathing faster and he turns to the window, closing his eyes. It is clear that the song, sung so gently, is transporting him back to happier times. Then, as Davis finishes singing, Hugh snaps out of his reverie and resumes his look of utter disappointment in his son, then soils himself.

Davis sings the song in a far more wistful way than the original and it’s a tender and very sad scene, a wayward son trying to reach his estranged father in the only way he knows how: through song. For a brief instant, as the old man feels the salt on his skin and the wind in his air, there is a connection. But then the song ends and the connection is lost. Whatever happened between them in the past, their relationship has run out of time.

Miller’s Crossing - The Danny Boy Shootout

Ageing Irish mobster Leo (Albert Finney) makes an enemy of another crime boss, Johnny Caspar (Jon Polito), against the advice of his laconic right-hand-man Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne). As a violent turf war ensues, Caspar’s goons descend on Leo’s house to take him out. But they discover to their cost that the old man is still pretty handy with a Tommy Gun.

What comes next is one of the Coen Brothers’ most celebrated set pieces, displaying their knack for choreographing a scene to the perfectly chosen song. Leo is chilling in bed with a nice cigar as he listens to Frank Patterson’s rendition of “Danny Boy” on the gramophone. Downstairs, his two would-be assassins enter, murder Leo’s bodyguard, and ascend the stairs towards his bedroom armed with Thompson submachine guns.

Fortunately for Leo, the deceased bodyguard’s cigarette has started a blaze and he is alerted to the danger by smoke rising up through the floorboards. This gives him enough time to grab his revolver and spring into deadly survival mode, making short work of the assassins before blowing up their getaway car with one of their Tommy Guns.

As the scene escalates, we get bursts of gruesome violence and macabre humour before the tune and the shootout soar to their conclusion and Leo stands triumphant in the street, chomping on his cigar in victory.

The Big Lebowski - Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)

The Big Lebowski is one of my favourite movies, so there was only ever one real choice when it came to picking the number one spot in this list: The “Gutterballs” dance sequence is one of those scenes that makes me brim over with joy, and feel just a little high whether I’m straight or sober.

It comes after the Dude’s befuddled kidnapping investigation leads to the swanky beachfront villa of porn baron Jackie Treehorn (Ben Gazzara). Treenhorn doesn’t believe his story and spikes the Dude’s White Russian, sending him into a delirious fever dream.

This lavish fantasy musical sequence is a real showstopper set in the celestial bowling alley of the Dude’s wildest dreams. At first glance, it seems pretty wild and random, but it draws in many elements from the plot and cultural references. The scene’s title, “Gutterballs,” references Treehorn’s porn empire, with the none-too-subtle image of a bowling pin sliding between a pair of bowling balls. Saddam Hussein mans the shoe rental desk, calling back to earlier news footage of the first Iraq war and the Saddam-a-like who works at the Dude’s local bowling alley.

There are a few references for movie buffs, too. The elaborate choreography is a homage to the Busby Berkley musical extravaganzas of the ‘30s, and the endless staircase rising up into the starry sky is a nod to the Powell and Pressburger classic A Matter of Life and Death.

To top it all off, the scene is set to one of the Coens’ greatest needle drops, “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)” from Kenny Rogers and the First Edition. It’s the perfect tune to compliment the trippy action but, like anything the Coens do, it isn’t totally at random. The song was a hit in 1968 and clearly describes an LSD trip, synching up with the Dude’s younger years as a politically engaged student dabbling with all sorts of drugs; “To tell you the truth, I don’t remember most of it.”

So there is plenty to dig into in the scene, but the best way to enjoy it is sitting back and revelling in the zany bravura of it all.

So there you have it, my top 10 picks of the Coen Brothers’ best scenes. What did I miss out, and what are your favourites? Let us know!