Just about anyone who has come into regular contact with movies knows the basic tropes of classic Film Noir: The world-weary protagonist, the femme fatale, the shadow-haunted city, the sinister underworld characters, the venetian blinds, and so on. The two films that helped crystalize the classic iconography and hard-bitten vibe were arguably The Maltese Falcon and Double Indemnity.

John Huston’s steely adaptation of Dashiel Hammett’s novel gave Humphrey Bogart a major breakthrough after years of playing tough guys and bit parts, playing private eye Sam Spade. The role of the cynical sleuth, reinforced by starring as Philip Marlowe in The Big Sleep, was such a perfect fit for Bogie that it’s this persona that the silver screen icon is best known for today.

Meanwhile, Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity gave us the classic tawdry tale of a wisecracking dupe fatally beguiled by a greedy femme fatale who just needs a little help murdering her husband. The Oscar-nominated screenplay, co-written by Wilder and Raymond Chandler, gave us all the snappy dialogue we now come to expect from Classic Noir.

Yet while these two touchstones may have popularised the tropes we’re so familiar with, Classic Noir ranged further and wider. You have Edward G. Robinson’s gentlemanly but gullible amateur artist preyed upon by criminals in Scarlet Street; Joseph Cotten on the trail of his racketeer friend in bombed-out Vienna in The Third Man; or Richard Widmark’s sleazy chancer looking for a score in Old London Town in Night and the City.

The impact of Film Noir on modern cinema can’t be overstated, but it was itself influenced by an earlier cinematic movement. Its iconic visual style is a descendant of German Expressionism, brought over to Hollywood by European directors like Fritz Lang, Michael Curtiz, and Billy Wilder, all of whom would play key roles in the development of Noir.

You can see in this shot from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari the striking interplay of light and shade and off-kilter composition that we often see in more stylised classic noirs:

Just as Film Noir wouldn’t exist without German Expressionism, we wouldn’t have Neo Noir without its Classic counterpart. Emerging in the late ‘60s, Neo Noir is sometimes harder to define, largely because directors and screenwriters were teasing and subverting an already amorphous box of toys. Here are a few of my favourite examples.

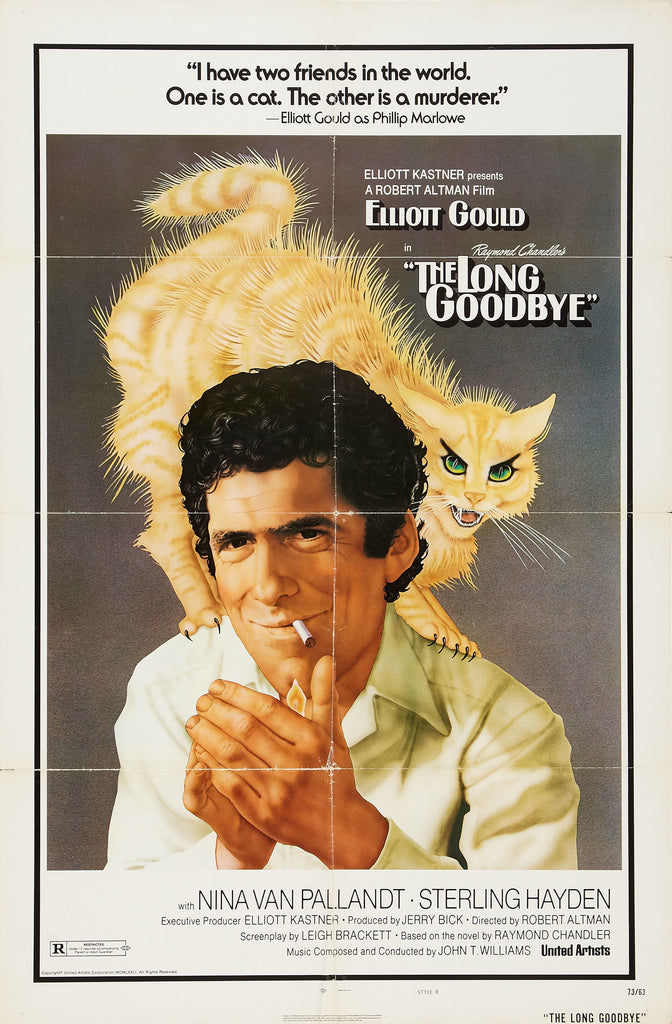

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Robert Altman’s offbeat adaptation of The Long Goodbye came out just 20 years after Raymond Chandler’s novel hit the shelves, by which time the world was a very different place. The film’s masterstroke is plucking Philip Marlowe out of the ‘50s and dropping him into the early ‘70s, where “Rip Van Marlowe” acts like he has woken up after two decades and wanders around Los Angeles as if nothing has changed.

More concerned with lighting his next cigarette than looking for clues, Elliot Gould’s ambling sleuth hardly notices that the dames next door are now hippie chicks smoking weed and doing topless yoga, and his high-end clientele now live in Bohemian beach communities instead of mansions out in the valleys.

Altman’s jazzy interpretation of the mystery and Gould’s irreverent riff on Marlowe provoked outright hostility from some critics at the time, but both were in keeping with the author and his famous detective. Chandler once said the perfect mystery was one you’d keep reading even if the last few pages were missing, and Altman rightly directs as if the journey and the vibe are the most important things in hard-boiled fiction.

Gould’s performance also isn’t as disrespectful as some seemed to think. Marlowe was never a classic genius detective like Sherlock Holmes or Hercule Poirot; he’s a solitary man of the streets who often finds himself a step behind the plot, beaten up by bad guys and leaned on by regular cops. Rather than make brilliant leaps of logic, he uses his smarts to doggedly needle his way to a case’s forlorn conclusion. In that respect, Gould’s Marlowe may just be my favourite screen version of the detective.

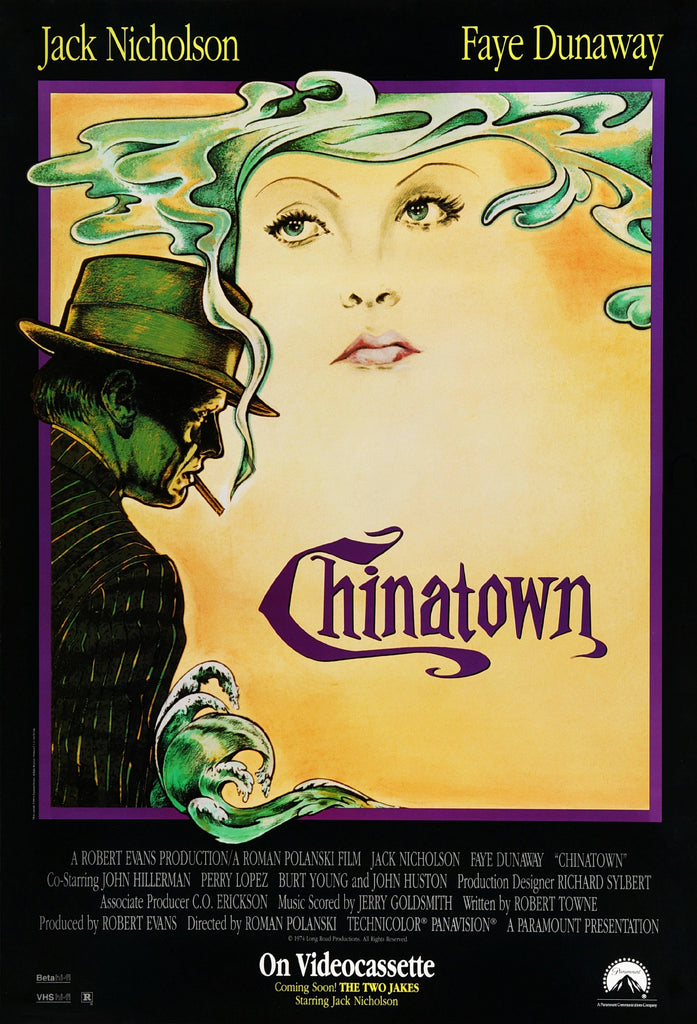

Chinatown (1974)

Roman Polanski’s Chinatown is one of the first names people reach for when it comes to Neo Noir, although at first glance it looks and feels very faithful to Classic Noir. Jack Nicholson delivers one of his earliest signature roles as private detective Jake Gittes, who takes what seems at first to be a simple infidelity case and becomes embroiled in a State-wide conspiracy.

Chinatown’s period setting is impeccable and, along with Rosemary’s Baby, shows how assured Polanski could be when working with a great screenplay. Chinatown reveals itself as a movie very much of its time at the end; while Classic Noir often had downbeat conclusions, the film concludes with a shrug of abject hopelessness: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” The implication is that corruption and violence is so ingrained in society that we might as well not bother trying to change it, which must have been how many Americans felt after a decade of high-profile assassinations, the Vietnam war, and the Watergate scandal.

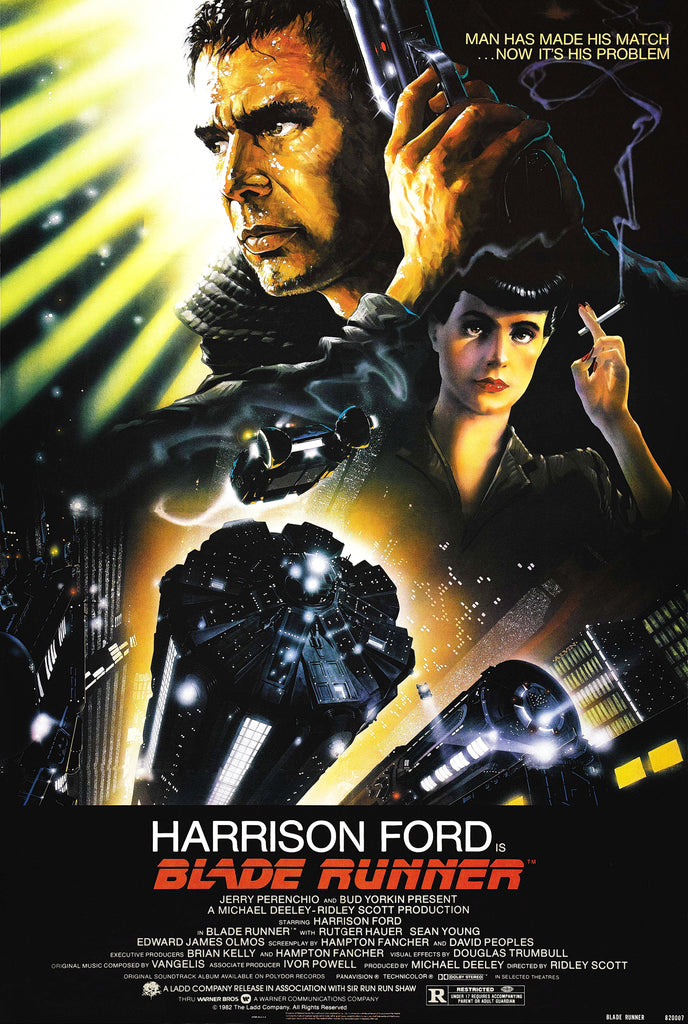

Blade Runner (1982)

Blade Runner took noir tropes into the future, where they sit beautifully alongside flying cars and giant Atari billboards in Ridley Scott’s celebrated dystopian sci-fi vision. Harrison Ford’s Deckard is a typical noir sleuth, right down to the awkward voiceover that was chopped from later cuts, while Sean Young’s Rachael is a clear homage to the femme fatales of old, all the way down to her retro hairstyle and dress sense.

Behind the camera, Scott has always been a very visual director. Working with cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, he creates a sumptuous, fully realised world, playing with light and shade probably better than any other Neo Noir.

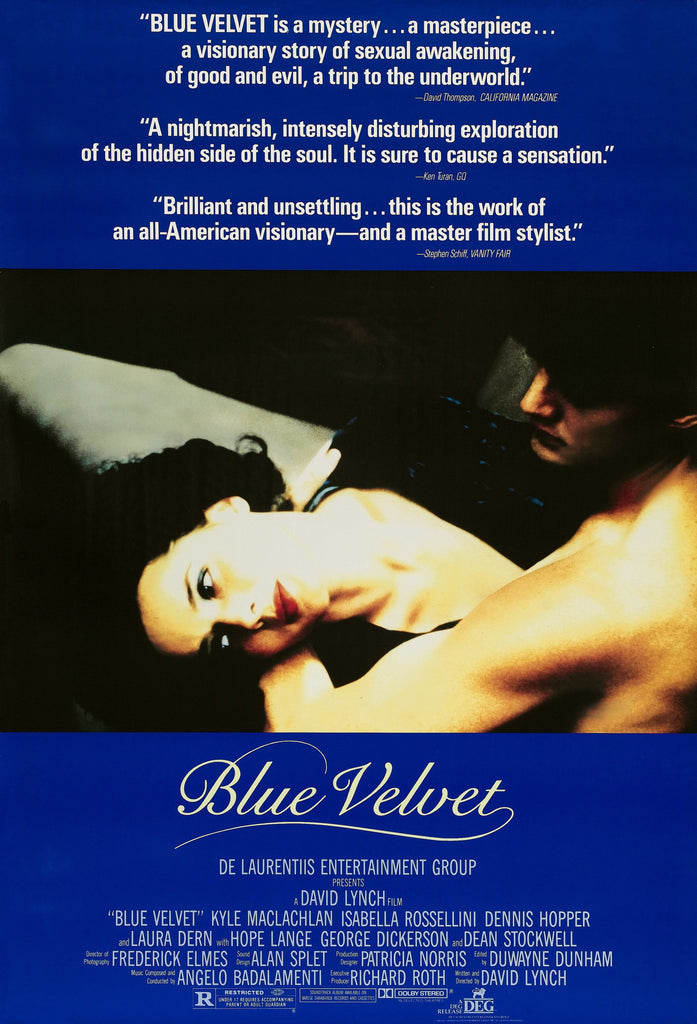

Blue Velvet (1986)

Classic Noir explored far darker and racier themes than many mainstream Hollywood movies dared, but the relaxation of restrictions on sex and violence allowed Neo Noir to venture into even more challenging territories.

Blue Velvet burrows beneath the facile surface of white-picket-fence Americana to wallow in the seedy and dangerous underworld beneath. Jeffrey (Kyle MacLachlan) is straight-edge student who finds himself drawn into a sado-masochistic affair with Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossalini), an abused torch singer, after he discovers a severed ear.

Sinking deeper into this strange twilight world which is only a stone’s throw from the safe life he knows, boundaries of voyeurism and sexual deviancy are crossed, bringing Jeffrey to the attention of the psychotic gangster Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper). Blue Velvet is one of David Lynch’s most accessible films without sacrificing his trademark weirdness, with unforgettable performances from Rossalini and Hopper.

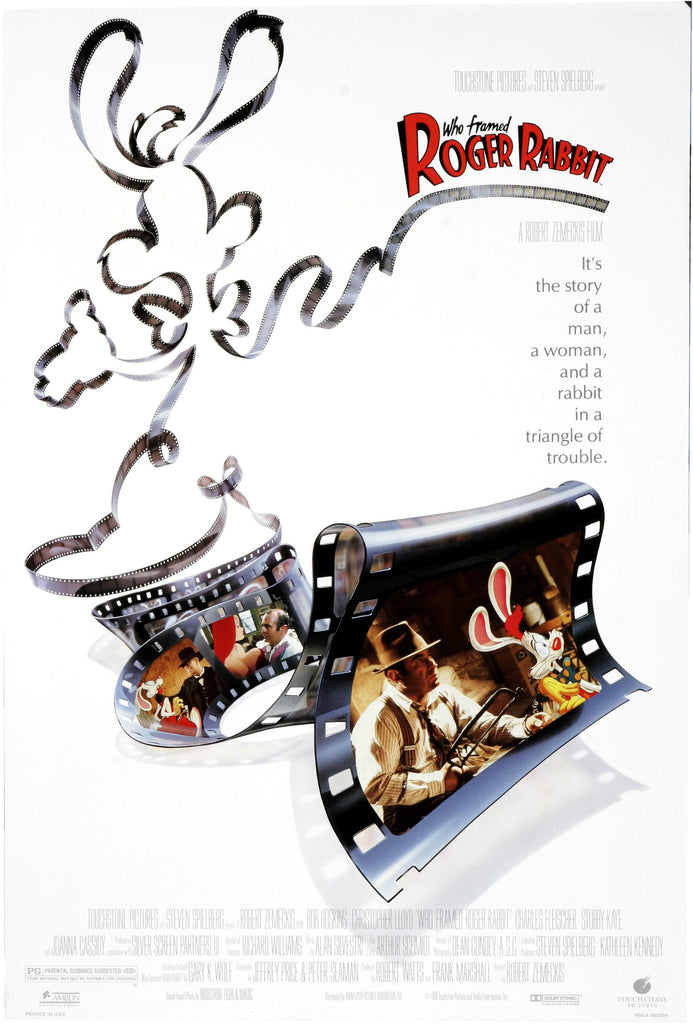

Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)

Around the same time that Classic Noir was becoming fully established as a genre, another wildly different artform was entering its Golden Era. Originally produced as a little light entertainment before the main feature, the Looney Tunes of Tex Avery and Chuck Jones helped Bugs Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and a whole roster of characters become cinematic icons in their own right.

It’s hard to imagine two genres so contrasting - mean and dark Film Noir vs wacky and colourful ‘Toons - but they blended perfectly in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? A film that served as both a loving pastiche of Noir and a celebration of the Looney Tunes’ exuberant anarchy.

Hot on the heels of Back to the Future, Robert Zemeckis took almost two years to complete the project, with the longest period spent in post-production matching animated characters to live action scenes. Putting animated figures in the same frame as real actors has been done before and since, but never so flawlessly. On a recent re-watch with the kids, I realised about halfway through that my disbelief was fully suspended and I was unquestioningly accepting Bob Hoskins talking to a cartoon rabbit.

The technological aspects of Who Framed Roger Rabbit? are ground-breaking, but it’s also a rollicking good time, too. The central mystery is generic, but who cares when a movie is so much fun? The human cast, also including Christopher Lloyd as the obvious villain, try their best to keep up with their animated co-stars and do a pretty good job. Kathleen Turner, who made her name playing femme fatales in Body Heat and The Man With Two Brains, is perfectly cast as the sultry voice of Jessica Rabbit, a shapely Toon who isn’t bad, she’s just drawn that way.

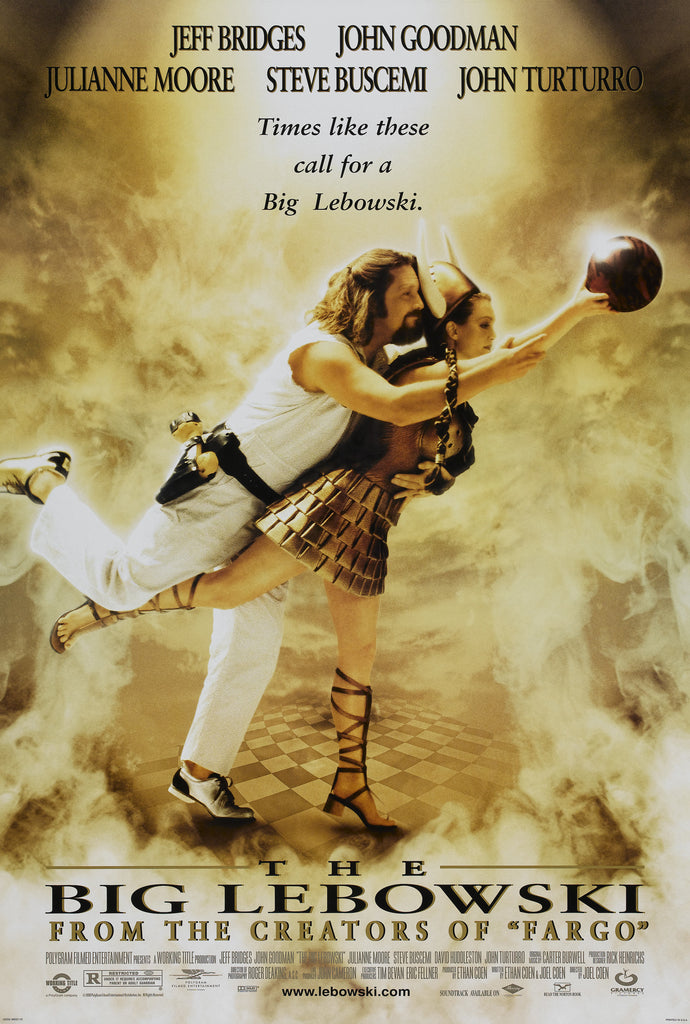

The Big Lebowski (1998)

The Coen Brothers love a bit of Noir: Their pitch black debut, Blood Simple, was pure noir, while Fargo and Burn After Reading were further original takes on the genre. Then you have their loose trilogy of films that put their own idiosyncratic spin on three classic hard-boiled authors: Dashiel Hammett (Miller’s Crossing), Raymond Chandler (The Big Lebowski), and James M. Cain (The Man Who Wasn’t There).

The middle film of this trio is their most irreverent approach so far, replacing Chandler’s dogged Marlowe with Jeffrey “The Dude” Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), a stoner bumbling his way through a labyrinthine kidnapping plot after some goons mistake him for his millionaire namesake and urinate on his rug.

The world of The Big Lebowski is strangely faithful to that of Chandler’s novels, as his mysteries often brought Marlowe into contact with many weird subsections of Los Angeles society. The character of The Dude is anything but faithful, as his involvement in the scheme only serves to muddy the waters as he shambles from one outlandish encounter to the next, meeting pornographers, German Nihilists, and a “Brother Shamus” along the way… no, not an Irish Monk.

Received with middling reviews at the time, The Big Lebowski has become a certified cult classic and stoner favourite since.

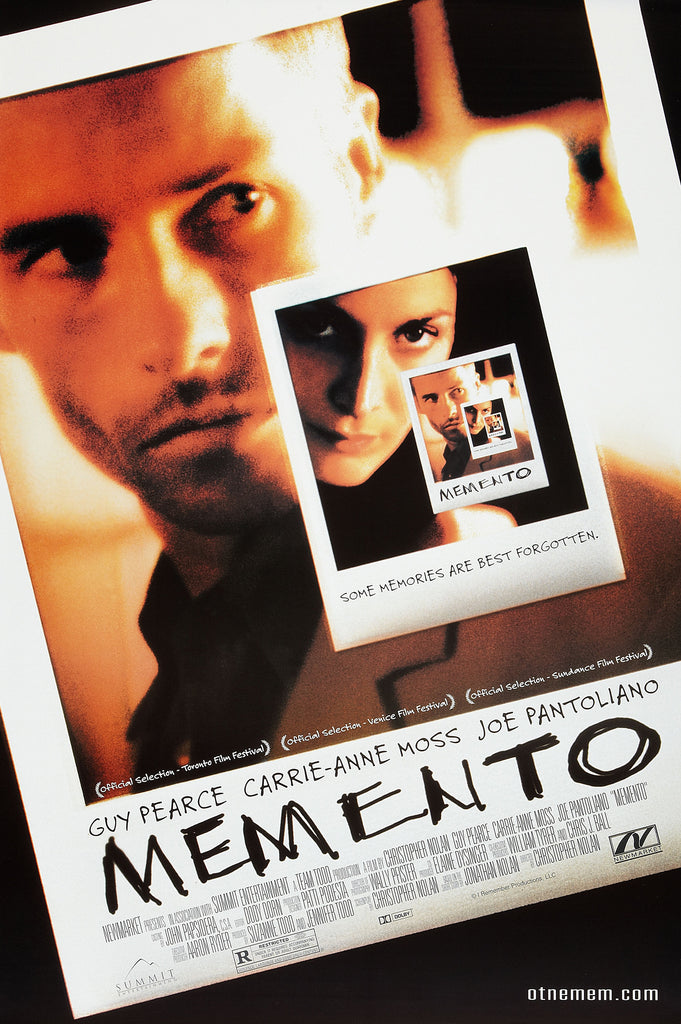

Memento (2000)

Film Noir traditionally involved a mystery that may or may not be resolved by the end of the movie. So what better way to radically invert that set-up than to start the story at its conclusion and work backwards to the start?

That’s the premise of Christopher Nolan’s ground-breaking second feature, a film that left me stumbling dazed out into the car park at the time, blinking, as if I was seeing the world anew. Like M. Night Shymalyan has become the Twist Ending guy, Nolan has since become the Messing-About-With-Time guy, but by far his boldest and most accomplished temporal experiment is Memento.

Another radical departure was creating a sleuth who can’t form new memories and can only recall events in short ten-minute bursts before everything fades, a part played with winning vulnerability and determination by a never-better Guy Pearce. Nolan added another element to his high-wire act by intertwining the reverse-order narrative with a second strand that moves forward in time, pulling off the whole stunt with incredible aplomb.

Memento is perhaps the ultimate puzzle-box movie, but it is also infused with far more heart and humour than many of Nolan’s other films to date. I return to it again and again, not just to marvel at the intricacies of the plot, but also for the characters and the aching poignancy of the story.

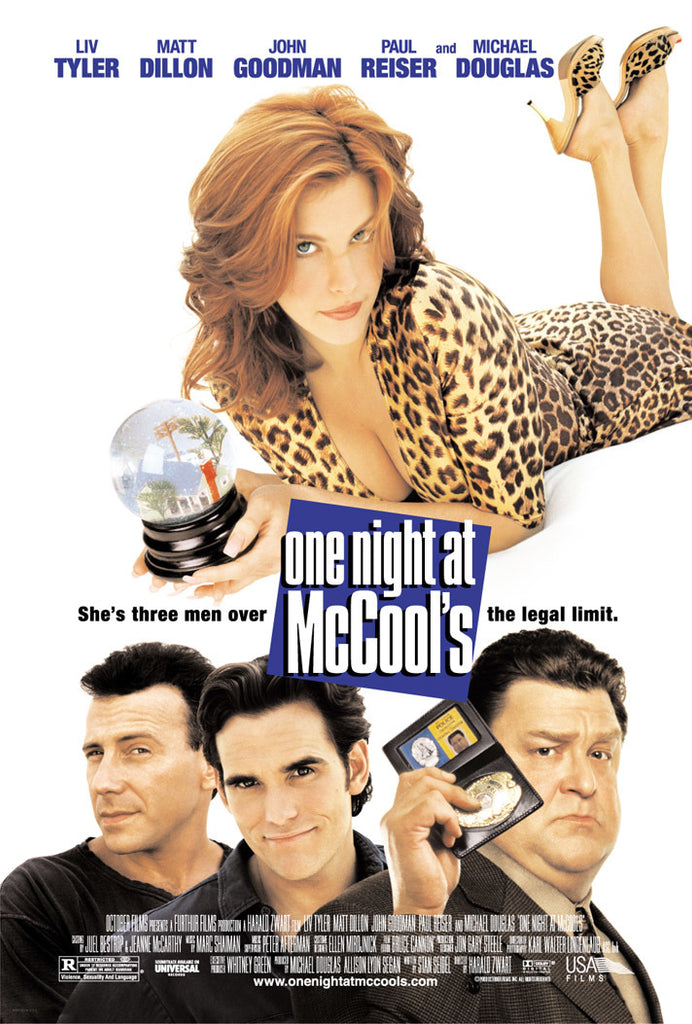

One Night at McCool’s (2001)

One Night at McCool’s isn’t a great movie, but it is one of my guilty pleasures. Liv Tyler stars as a man-eater who manipulates three very different male dupes: Matt Dillon’s down-at-heel every guy, John Goodman’s grieving traffic cop, and Paul Reiser’s sleazy family man out looking for kinky kicks.

The humour is broad and smutty, but the most interesting thing about the film is how it unfolds the story Rashomon-style, told from the alternating perspectives of three stooges absolutely transfixed by this femme fatale. An added bonus is Michael Douglas: He might not be best known for his comic chops, but he’s very funny as a ridiculously coiffed hitman who conducts his business from a bingo hall.

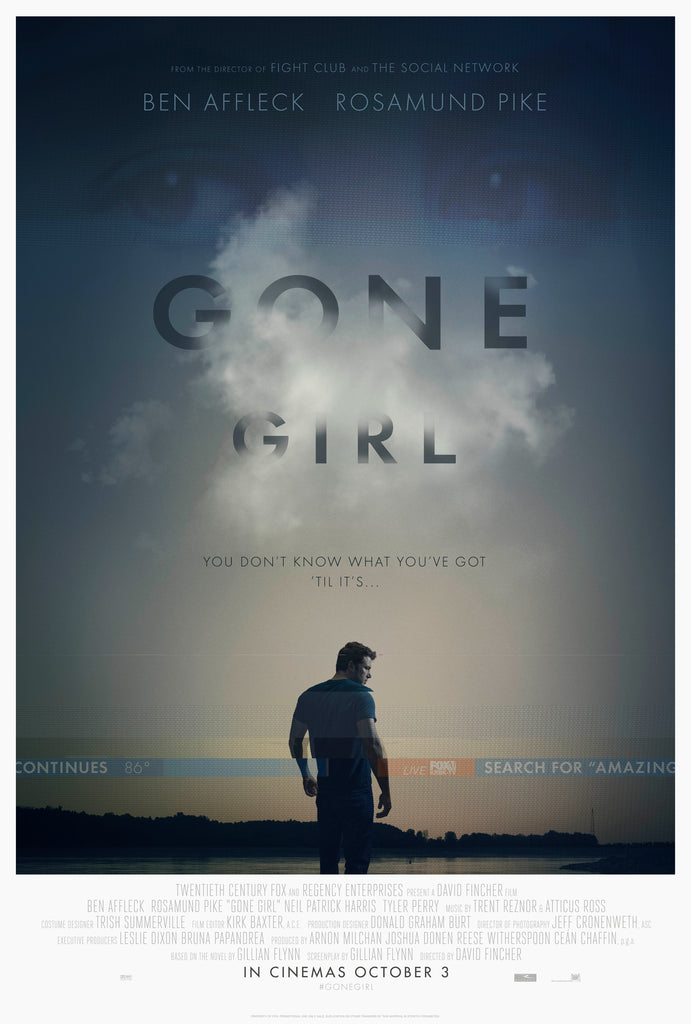

Gone Girl (2014)

David Fincher dabbled with aspects of the genre in Seven, Zodiac, and The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo, but Gone Girl is his outright Neo Noir masterpiece. Gillian Flynn’s meticulous screenplay, adapted from her own page-turner, flips the script on the typical femme fatale and unreliable narrator beats, telling the story from the perspective of Amy (Rosamund Pike), a nasty piece of work concocting a scheme to frame her husband for her own murder.

Gone Girl plays on Ben Affleck’s tarnished heartthrob image to great effect, even making a key plot point of that famously dimpled chin, but the movie is all about Amy, played to mesmerising perfection by Pike in her best performance to date. Behind the camera, riveting control of the story shows how, at his best, Fincher is one of modern cinema’s most accomplished directors.

Inherent Vice (2014)

Speaking of accomplished modern directors, Paul Thomas Anderson has become practically his own genre since making his debut with Hard Eight in 1996. Inherent Vice is one of his most loosely structured films, a weird shaggy beast that filters Thomas Pynchon’s novel by way of The Big Lebowski, by way of Anderson’s own distinct sensibilities.

Playing stoner private eye Doc Sportello, Joaquin Phoenix is at his most daringly freeform, seemingly making up his performance as he goes along. Like Lebowski, Raymond Chandler is the most obvious point of reference, another convoluted mystery almost for the sake of having a convoluted mystery.

Anderson indulges in the film’s weed-dazed vibe, meandering from one weirdo plot point to the next with absolutely no sense of urgency. That earlier Chandler quote about the missing pages feels especially apt here: I’ve seen Inherent Vice three times and still couldn’t even begin to tell you what happens. It’s all about the atmosphere.

The Nice Guys (2016)

Shane Black has been toying with variations on the Noir formula for three decades now, from The Last Boy Scout to Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. The Nice Guys is arguably his most successful, as well as his most outright hilarious.

Surly old Russel Crowe is a revelation in his best performance since Gladiator, showing an unexpectedly deft comic touch as a lowdown arm-breaker of a thug-for-hire, while Ryan Gosling deserved an Oscar nod for his brilliantly light-footed turn as an alcoholic sleuth trying to get to the bottom of a porn star’s untimely demise.

Black can write this mismatched buddy stuff in his sleep, but the chemistry between the two actors here is spectacular. The mystery itself is almost beside the point as they bicker and bond against the twinkling backdrop of ‘70s Los Angeles, positively humming with Boogie Nights-style energy.

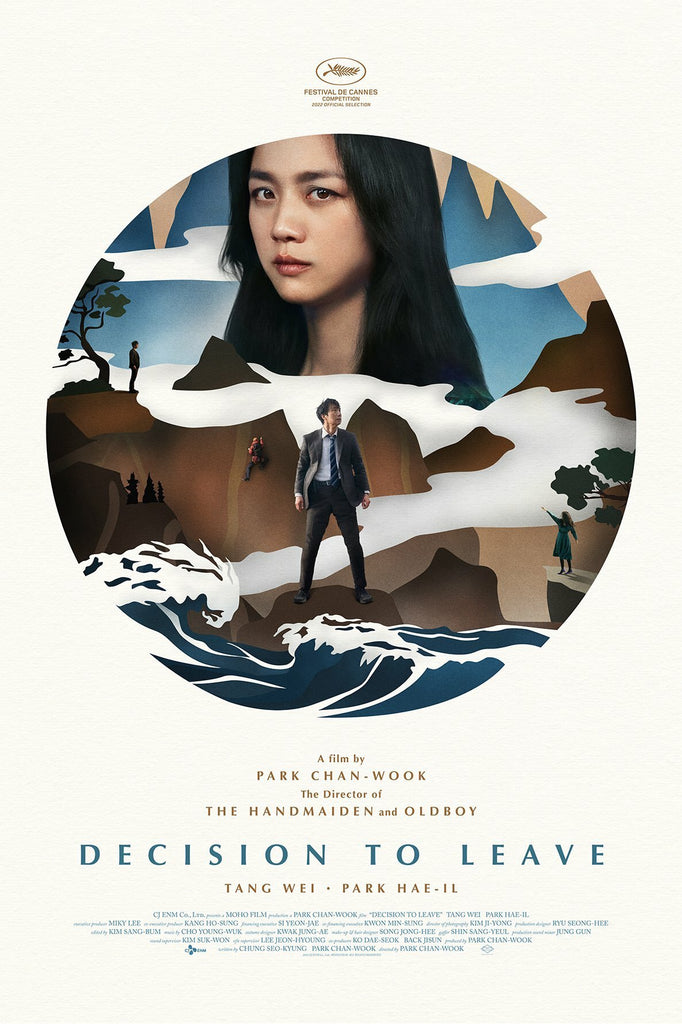

Decision to Leave (2022)

A big hit at Cannes this year, Decision to Leave might be the next South Korean masterpiece to break into the Western mainstream after the Oscar-winning triumph of Parasite a few years back. Park Chan-Wook’s first feature since The Handmaiden in 2016, it’s a meticulously crafted thriller that combines Hitchcockian obsessions with coolly noirish plot.

I saw the film at Karlovy Vary Film Festival, and the whole audience was gripped from the opening frames. It’s the work of a master storyteller at the top of his game, following a fastidious detective who becomes dangerously involved with the mysterious widow of a man who dies from a suspicious climbing accident.

Decision to Leave has a unique style all of its own, feeling retro while also successfully integrating modern technology into a classic murder plot. Chan-Wook is clearly enjoying himself, wrapping up one mystery by around the halfway point before launching into another and delivering a finale that is both emotionally devastating and completely satisfying.

South Korea has been producing some of the most eye-catching and riveting cinema of the past two decades, and Decision to Leave is among the best.

So there you have it, a few of my favourite Neo-Noirs. What are your favourites? Let us know!