Documentaries have enjoyed something of a facelift since the turn of the century, and Michael Moore had a large hand in that. He’s a divisive figure no matter which side of the political fence you’re on, but his polemical films Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) made documentaries true multiplex contenders that got everyone talking, garnering awards and capturing the attention of both audiences and critics.

Suddenly, documentaries were hot and the success of Moore’s films, along with the unexpected box office success of Super Size Me (2004), paved the way for a golden age of documentary filmmaking. At least in terms of availability and watchability.

I’ve been on a bit of a documentary binge lately since I started making my own short film about a street poet here in Brno, CZ. I wanted to see how the pros did it and I realised once again what a fantastically diverse genre it is. Here are some of my favourites.

(Please note: My picks are mainly documentaries about adventurers, eccentrics, pioneers, artists, and dreamers. You’ll find nothing about war, genocide, politics, or true crime in this list. Those are for another article.)

Deep Water (2006)

Deep Water is the stranger-than-fiction tale of Donald Crowhurst, a middle-aged amateur sailor who took part in a non-stop round-the-world sailing race to save his ailing business and stave off financial ruin. Unfortunately for him, Crowhurst was only a mediocre sailor at best, taking to the open ocean in a supposedly revolutionary trimaran that was barely seaworthy.

Realising that taking on the treacherous Southern Ocean in such a vessel would be suicide, Crowhurst hatched a cunning plan. He would hang out in the Atlantic for a few months, keep a fake log of his journey, and wait for the other competitors to complete their lap of the globe so he could drop in behind them and finish the race without arousing too much suspicion.

In the meantime, alone on his boat for many months wrestling with his deception, Crowhurst went a bit mad, devising crackpot theories that the cosmos was out to get him. When you find out the cruel twist of fate that finally scuppered his scheme, you might tend to agree with him.

Put together using Crowhurst’s eerie video footage and tape recordings, Deep Water is a disquieting adventure that explores the limits of human endeavour, fallibility, and folly, and one that captures the humbling vastness of the ocean.

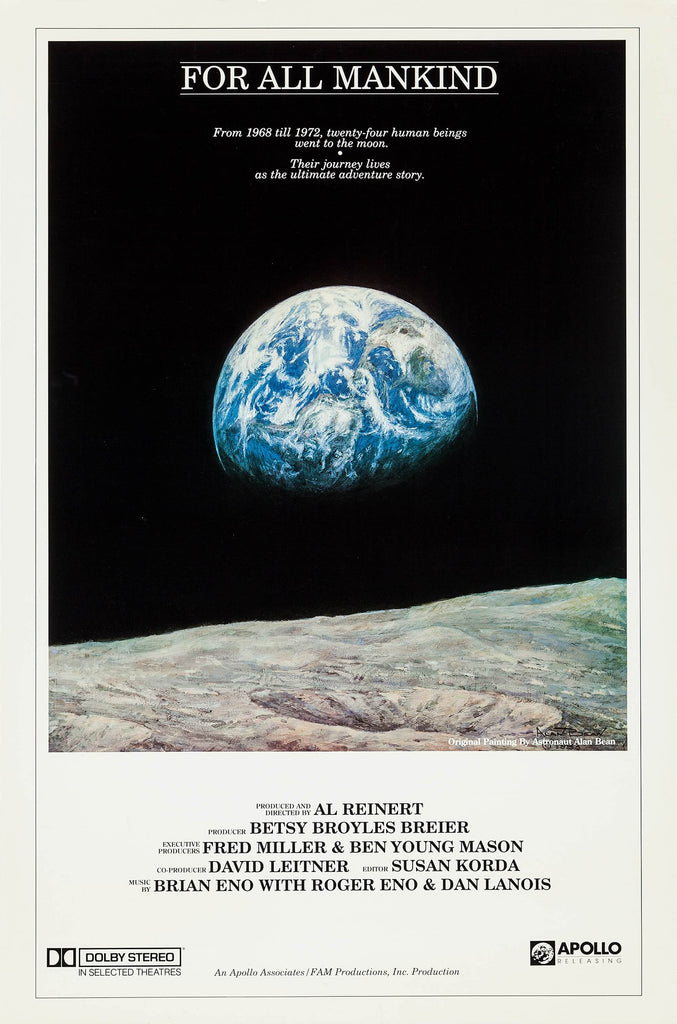

For All Mankind (1989)

We all know Neil Armstrong’s famous words as he first set foot on the moon, but the line that stood out for me in Al Reinert’s For All Mankind is far more modest. “Y’all take care now!” chirps an unseen woman in a Cape Canaveral corridor as three astronauts make their way to the launchpad, fully decked out in their space suits. She makes it sound like they’re off on a weekend fishing trip rather than travelling to space.

That plucky and unsentimental line pretty much sums up the film. Bolted together from six million feet of NASA footage, it is workmanlike in the best possible sense, mirroring the focus and economy of the Apollo program itself. The astronauts are plainspeaking men with a job to do and the boys in the control room are there to get them to the moon and back with the minimum of fuss. In one scene, when a spacecraft springs a potentially deadly oxygen leak, both parties work with the problem as if it was no bigger deal than a flat tire.

The documentary shows the program for what it was: a massive undertaking that required a blend of the right stuff, incredible ingenuity, and pure blunt force. There is something quite brutal about strapping three guys to the top of a 300-foot cylinder filled with fuel, setting light to it, and blasting them off the planet. The footage of the rockets taking off is both awe-inspiring and terrifying, but once the astronauts are safely in space, they have time for moments of quiet contemplation and breath-taking views of the Earth. It never fails to amaze me how beautiful our planet is.

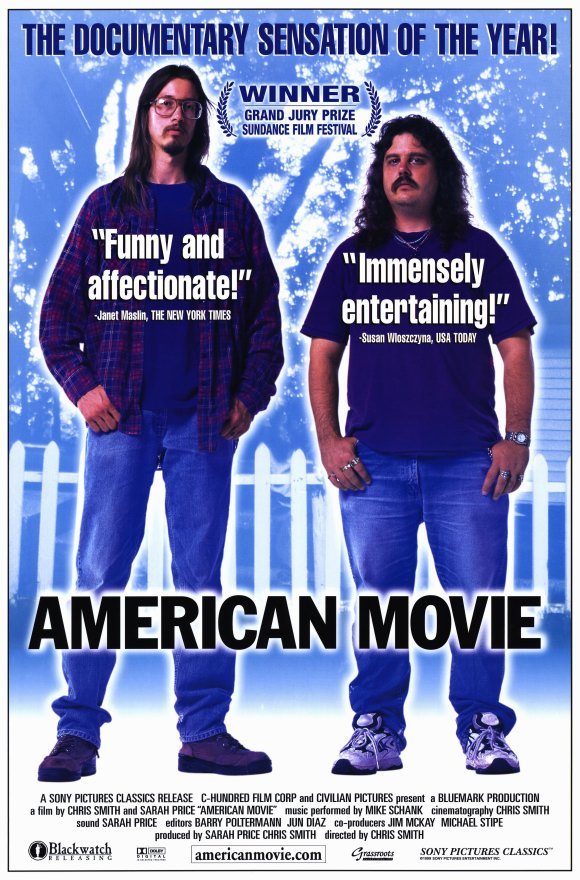

American Movie (1999)

Anyone who has ever thought about making their own film should see American Movie, Chris Smith’s hilarious and often sad documentary following Mark Borchardt, a hapless filmmaker from Wisconsin trying to get his dream project off the ground.

He wants to make a serious movie but he has no money, so he decides to complete a low-budget horror called Coven instead. The mishaps pile up as he battles with limited resources, lack of available talent, and trying to coral his family and friends who have agreed to star in the film.

Like Ed Wood, the notorious director of Plan 9 From Outer Space, Borchardt’s passion for cinema shines through and he seems to know his stuff, but he is beset from all sides by the circumstances of his life. Smith chooses to focus on the positives. Borchardt comes across as an energetic, engaging character who loves his family and friends, and pushes through to a triumphant premiere of his movie with dogged determination. Like the travails of Wood before him, the message is this: If this guy can get a film made, anyone can.

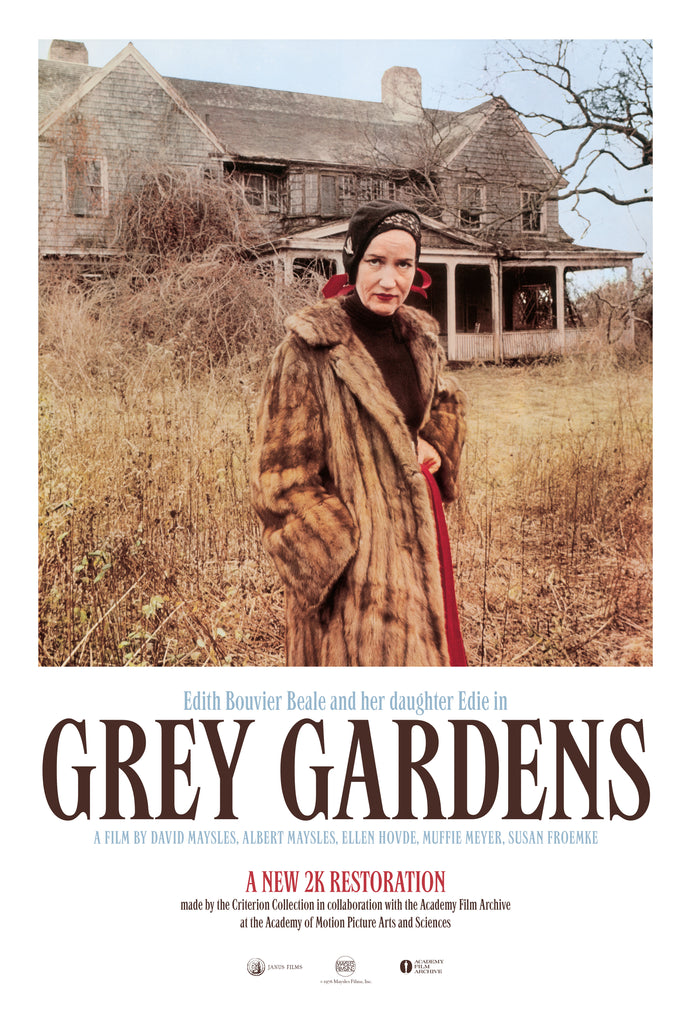

Grey Gardens (1976)

“It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present,” muses “Little” Edie Bouvier Beale in Grey Gardens, the Maysles Brothers’ celebrated documentary about two distant relatives of Jackie Kennedy living in squalor in the titular East Hampton mansion.

It’s also difficult for documentary makers to keep the line between observation and exploitation, and the film received criticism for the latter. Formerly from high society but now impoverished, Little Edie and her mother, Big Edie, made headlines for their appalling living conditions, with around 1000 bags of rubbish removed from the decrepit house.

When you see two grown women living in a draughty old mansion encrusted in dry cat piss, questions of mental health and the responsibility of the filmmakers to their subjects come into play.

Either way, both Big and Little Edie are natural born drama queens and apparently love the attention, hamming it up for the cameras as they reminisce, squabble, sing, and ponder lost love and opportunities. Little Edie is an especially fascinating subject, a true eccentric with a florid turn of phrase that makes her sound like a Tennessee Williams character.

Grey Gardens plays like a Gothic sitcom, and its camp factor has earned the film a cult following. Although it is frequently very funny, there is something haunting about two women rattling around a tumbledown house wondering what might have been, providing a keen study in co-dependency and thwarted dreams.

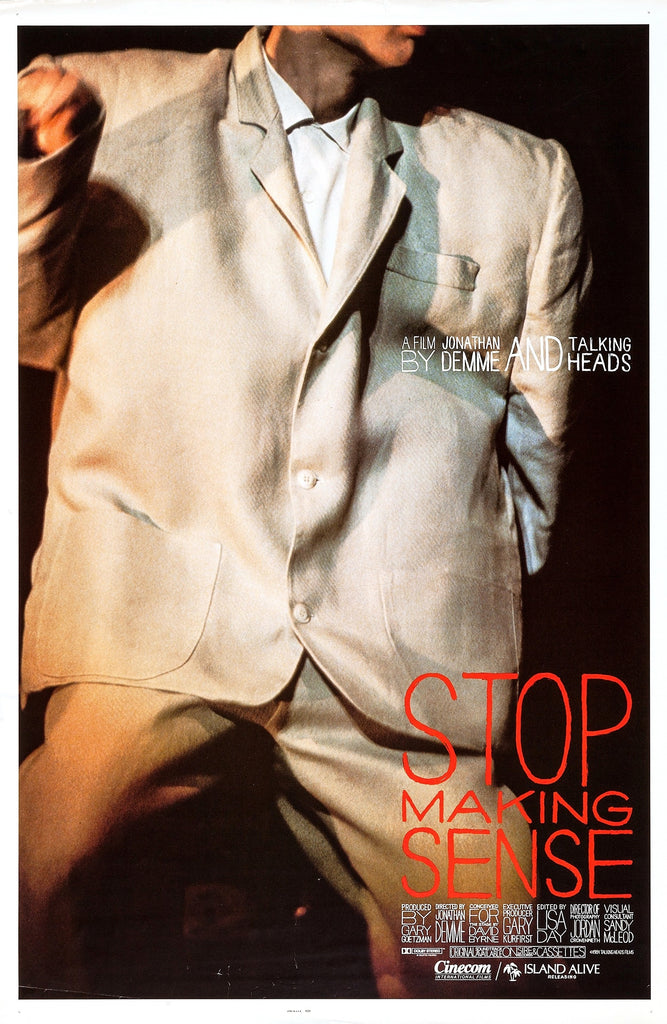

Stop Making Sense (1984)

David Byrne, the frontman of Talking Heads, walks onto a bare stage with an acoustic guitar and a cassette player. “Hi, I’ve got a tape I want to play,” he says, pushing the button. Byrne strums along and sings: the track is “Psycho Killer” and it's the start of a concert film unlike any other.

Over the course of 90 minutes, Jonathan Demme’s expertly edited documentary deconstructs the notion of a live music experience and reconstructs it again, literally. After Byrne’s solo song, he’s joined by a bassist on stage, followed by a drummer. Gradually, we watch a band put together piece by piece, often with technicians in the background setting up each instrument or wheeling on additional staging or lighting.

As the concert builds towards its joyous, life-affirming crescendo, the stage is filled with musicians, singers, and dancers, and now the marvel is seeing them riff off each other. Rather than a gimmick, Stop Making Sense is a celebration of the band’s virtuosity, and one that captures the sheer energy of a great live performance.

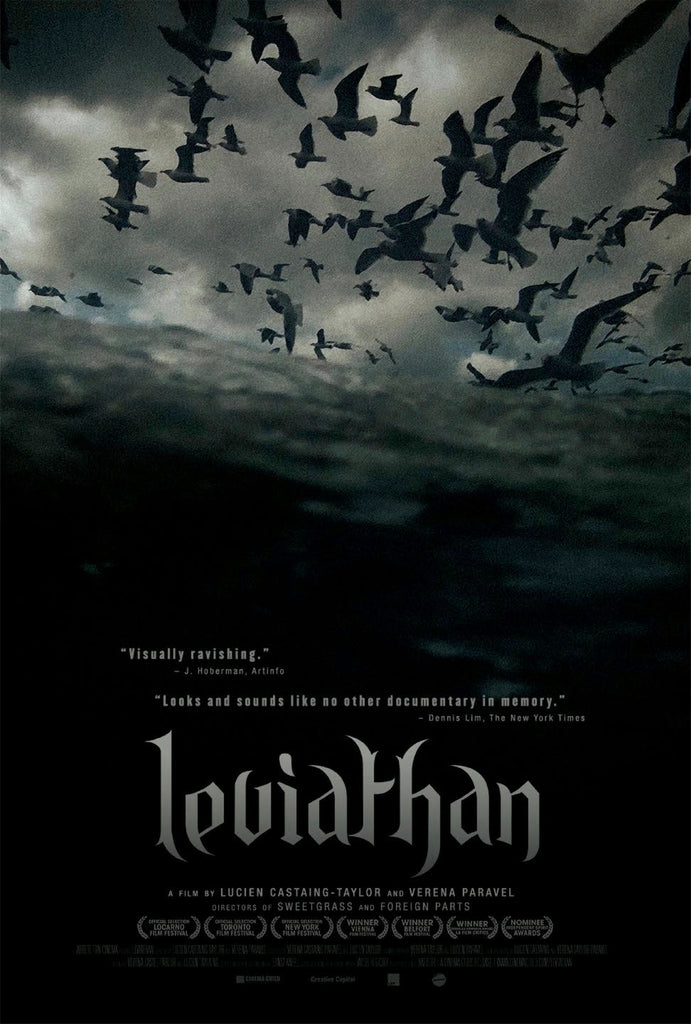

Leviathan (2012)

Some documentaries are so radical that they give you a totally different perspective on their subject. Leviathan started out as a straightforward insight into the fishing industry, but the filmmakers switched focus to give us a fish’s eye look at a Massachusetts trawler.

That change of viewpoint takes all the usual man-against-the-sea beats out of the equation and reveals the ship for what it is: A grisly floating steel abattoir that rips thousands of fish from the cold waves at a time and slaughters them on deck. When we do see the crew - grim, silent, exhausted - they are portrayed as robot-like components in the industrialised harvesting of the ocean.

Leviathan is a tough watch. There is no narrative, barely a human voice is heard throughout, and the filmmakers challenge the viewer with their experimental style. The fish-level POV was achieved by scattering GoPro cameras around the vessel and the effect is dizzying. We end up dangling upside down in nets, washed overboard, sent skidding across the deck, and hauled up among the catch. It’s a film that requires fortitude but it’s an experience unlikely to be forgotten.

Honeyland (2019)

Another beauty of documentaries is that they can introduce us to subjects that we haven’t even thought about before, let alone watched a movie on. One such documentary is Honeyland, the film about North Macedonian beekeepers that I never knew I needed.

Directors Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov and their team spent three years shooting in a remote mountain village, following the day-to-day life of Hatidže Muratova, a middle-aged beekeeper who shared a basic stone hut with her elderly mother.

The filmmakers’ fly-on-the-wall style is all but invisible, allowing us to get fully absorbed into Muratova’s routines as she collects honey from wild bees in the area and sells it for a modest profit in the capital city, Skopje. She’s a forthright and engaging character who deeply respects the bees and their environment, always leaving half the honeycomb to keep the insects happy and productive.

The gentle tone takes on a more culture-clash edge when a nomadic family moves into the village and also takes up beekeeping. Unlike Muratova’s traditional methods, the father is intent on plundering his hives for as much honey as possible.

Honeyland comes with a strong in-built environmental message, warning against the exploitation of natural resources and consumerist greed. Or, if you just want to chill and enjoy the wonderful vistas, it also plays as an unconventional hang-out movie about a woman, her mum, and her bees.

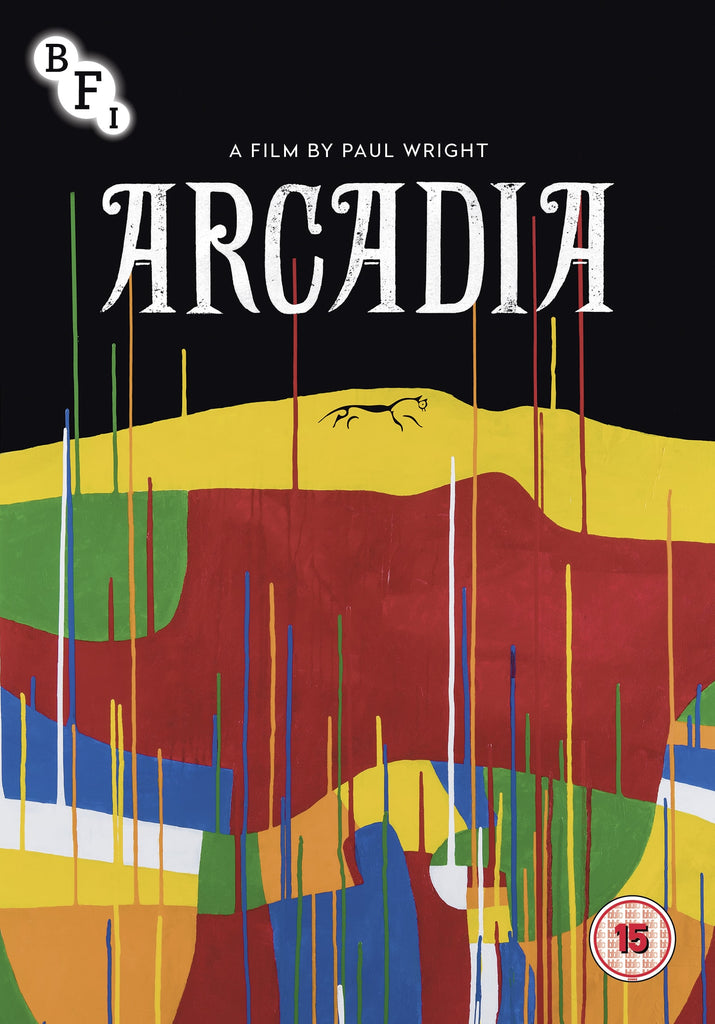

Arcadia (2017)

The folk horror genre, in its British form, plays on the dissonance between urban and rural, modern and old, the present and the past. Plotlines often see city-dwellers visiting a remote patch of countryside and falling foul of the customs of country folk, tapping into an urbanite’s unease about the landscape that lies beyond their towns and cities.

Paul Wright’s Arcadia explores this sometimes uneasy relationship between the British and their land with footage mined from 100 years of the BFI’s rural archive, clashing images of the modern world with eerie snapshots of old traditions, folk dance, harvest festivals, and forgotten rituals. The result is a hypnotic folk horror montage that is both entrancing and creepy, aided immensely by the trippy score from Adrian Utley of Portishead and Will Gregory of Goldfrapp.

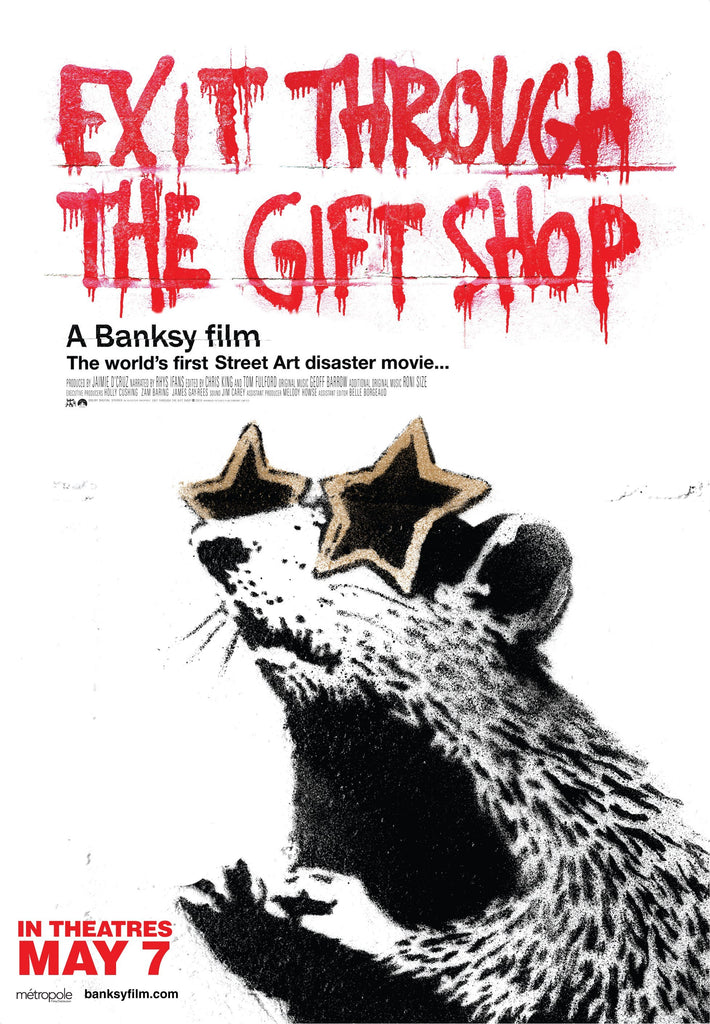

Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010)

Banksy trades on his anonymity and mystique, so how exactly does a documentary profile of him work? In typically evasive fashion, the famous street artist flips the camera on the man supposedly shooting the film and makes a documentary about him instead.

Exit Through the Gift Shop largely focuses on Thierry Guetta, a French artist living in LA who obsessively filmed every aspect of his life. On a visit to his home country, he discovers the illicit thrills of street art, setting on a course to become “Mr. Brainwash,” whose meteoric rise sold out exhibitions of his witless pop art. At one point Banksy, his voice altered and hidden in shadow like a witness on a true crime show, notes:

“Warhol repeated iconic images until they became meaningless, but there was still something iconic about them. Thierry really makes them meaningless.”

Some critics still debate whether Guetta was genuine or a PR stunt cooked up by Banksy for the film. Either way, making him the star gives the film an off-kilter perspective on the nature of art and celebrity. It’s also a frequently funny insight into the transient and illegal world of street art.

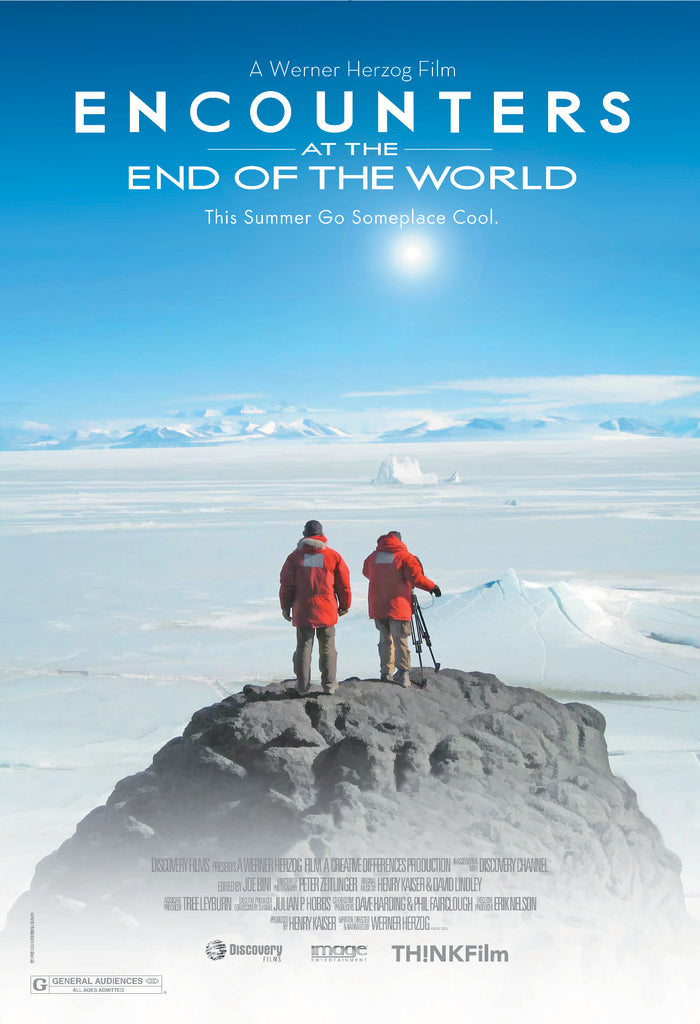

Encounters at the End of the World (2007)

Werner Herzog is well known for making himself part of his documentary narratives as much as the subjects he portrays. His interventions are wide-ranging, from his often-parodied philosophical musings to fictionalised accounts of real events, such as persuading former POW Dieter Dengler to re-stage his traumatic imprisonment in Little Dieter Needs to Fly.

My favourite Herzog documentary is Encounters at the End of the World, which finds him in puckish form as he travels to the Antarctic to spend time with the oddballs and misfits who accumulate at the bottom of the planet.

As with his harrowing condemnation of the death penalty, Into the Abyss, Herzog uses his digressional interview technique to get his subjects talking on tangents. This often reveals more about the subject at hand than a straightforward Q&A.

Based at the McMurdo research station, Herzog blends the sublime, ridiculous, and mundane. He interviews glaciologists, plumbers, cold water divers, and a man who is really into penguins; detours to an outdoor rock concert and a survival game called “bucketheads;” and delves beneath the ice to capture otherworldly footage of the strange creatures that swim there. It’s a film that evokes the wonder of our natural environment and celebrates the dreamers among us.

The Two Escobars (2010)

The world’s most popular team sport hasn’t got a lot of great movies to shout about. The best film I’ve seen so far about football is the Zimbalist Brother’s exhilarating ESPN 30 for 30 documentary The Two Escobars, which traces the link between the Colombian national team of the ‘90s and notorious drug lord Pablo Escobar.

The film centres on the tragedy of Pablo’s namesake, Andre Escobar, the upstanding team captain who played straight man to the roster of mercurial talent including eccentric goalie Rene Higuita, Carlos Valderrama and his iconic hair, and electrifying winger Faustino Asprilla. As the team found favour with the kingpin, a chain of events was set into motion that resulted in Andre’s fatal shooting after he scored the own goal that knocked Colombia out of the 1994 World Cup.

Using a dazzling array of footage, the Zimbalists manage something that few other films about the sport, fiction or nonfiction, have captured: the unpredictable rhythms of 22 men trying to knock a spherical object into their opponent’s net, roared on by the raucous tide of supporters in the stadium.

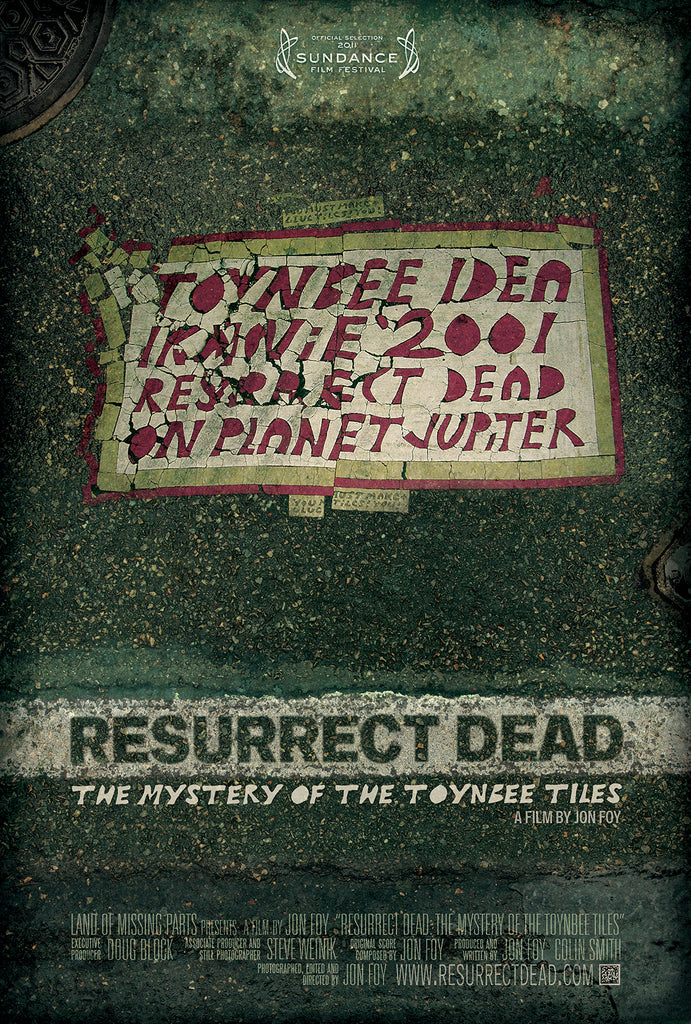

Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles (2011)

I love a good mystery, the stranger the better. I won’t claim that Resurrect Dead is anything more than workmanlike, but it does give us a great tale.

The film delves into the enigma of the so-called Toynbee Tiles, hundreds of hand-crafted cryptic messages that started appearing on city streets across America in the ‘80s. The majority of them read:

If the message was intriguing enough, their provenance proved even more of a mystery. No one could figure out how they appeared, seemingly out of nowhere, embedded in asphalt.

The eventual outcome of the doc is a thoughtful insight into editorial choice. Having tracked down the person they believed was responsible for the tiles, the filmmakers discovered the poignant motivation behind them… and decided to leave their creator well alone. It was a sensitive and responsible decision that also helped preserve the mystique of the peculiar messages.

Room 237 (2013)

The Shining is my favourite Stanley Kubrick movie. Not only is it a masterpiece of supernatural horror, it’s one of those movies that becomes ever more fascinating with the more you find out about it. Like the meticulous and labyrinthine design of the menacing Overlook Hotel, it contains a multitude of secrets and curiosities, some of which provide the basis for Rodney Ascher’s Room 237.

The film explores a range of fan theories that stem from various aspects of Kubrick’s haunted house tale. Some are enlightening, such as a study of the hotel’s floorplan that reveals it is an Escher-like maze that makes no logical sense. Others are bonkers, like the conspiracy theory that the movie is Kubrick’s admission that he faked the Apollo moon landing.

All in all, Room 237 is a fascinating trip down several rabbit holes that opens up ever more food for thought for lovers of the film, and a captivating journey into obsessive fandom.

So there you have it, 12 of my favourite documentary films of all time. What are your picks? Let us know!