30 years ago, a little crime movie called Reservoir Dogs made its premiere at Sundance Film Festival. It starred Harvey Keitel, who had fallen off the radar somewhat, and character actors like Michael Madsen and Steve Buscemi. More interestingly, who was this Quentin Tarantino guy, not only coming out of nowhere to write and direct, but also give himself the juicy opening monologue about Madonna’s “Like a Virgin?” And what the hell was a reservoir dog, anyway?

The tag team of Tarantino’s startling first feature and Robert Rodriguez’s El Mariachi came along at just the right time. While Steven Soderbergh’s Sex, Lies, and Videotape was the low-budget festival darling credited with kickstarting the indie film movement of the ‘90s, it was these two pulpy, in-yer-face crime flicks that really shook things up when Hollywood was becoming very staid and safe, with the Oscars awarding the likes of Driving Miss Daisy and Dances with Wolves the Best Picture prize in the previous few years. The arrival of these hip new movie geeks was arguably as influential as Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider in the late ‘60s, which ushered in the American New Wave of Coppola, Scorsese, Bogdanovich, Altman, and many others.

The story of how Tarantino got Reservoir Dogs to the screen is now legendary. He wrote the screenplay while working in a video store and originally intended to shoot it as a no-budget effort with his friends, but managed to get it to Harvey Keitel via mutual contacts. The actor saw the potential, and his clout helped Tarantino get a bigger budget and a roster of respectable actors to play some career-defining roles.

Tarantino certainly grasped the opportunity and directed the thing like he had dreamt every frame of it a thousand times over. Reservoir Dogs was the freshest and most invigorating opening statement in years, and clearly the work of an audacious new talent. It was our first glimpse of the world inside Tarantino’s head, a place of tough guys in sharp suits trading wise-ass dialogue, slow-motion walks, Mexican standoffs, and cool old tunes on the soundtrack. It was a world that would remain remarkably consistent with the development of the Tarantinoverse - Michael Madsen’s Vic Vega is the brother of John Travolta’s Vincent Vega in Pulp Fiction, for instance.

Tarantino also showed a complete grip of cinematic language from the outset, with bold non-linear storytelling and even having the balls to make a heist movie where we don’t even see the heist itself.

Reservoir Dogs became an instant pop cultural moment. You can see that impact in something like Doug Liman’s Swingers, another hip low-budget indie that might not have existed without Tarantino’s influence. Liman cheekily recreates two scenes from earlier movies: The single-take journey through the Copacabana in Goodfellas, and the camera roaming around the table of guys shooting the shit at the beginning of Reservoir Dogs. The message was clear: within a few short years, Tarantino was as quoteworthy for film buffs as a seasoned master like Scorsese.

Since his audacious debut, Tarantino has become one of the most influential directors of the past 30 years. That hasn’t always been a good thing; just take a look at the deluge of Pulp Fiction wannabes in the ‘90s like Killing Zoe and Suicide Kings. Tarantinoesque has become part of the lexicon as much as Hitchcockian, Spielbergian, or Altmanesque, and, like the portly Master of Suspense, there are few directors as instantly recognisable as their stars, with the goofy chinny grin and the rat-a-tat patter as he waxes lyrical about his favourite movies.

I don’t want to over-do the gushing, however. As much as I enjoy Tarantino’s movies, I’m often left with the nagging doubt that beyond the style, dialogue, music, set pieces, and memorable performances, they don’t really add up to much. I mean, beyond all the cool stuff, what does Tarantino actually have to say beyond “Hey, check out this awesome thing I borrowed from this amazing old movie?” Even as he has moved into weightier topics like slavery and the Holocaust, what does his revisionism achieve beyond indulging us all in a little wish-fulfilment?

Despite my misgivings, there can be little doubt that a new Tarantino movie is an event, a film that generates an insane amount of buzz and that everyone wants to see. Now we are coming towards the end; the director has stated he will make ten movies and retire. With nine already in the bag, what will be the tenth?

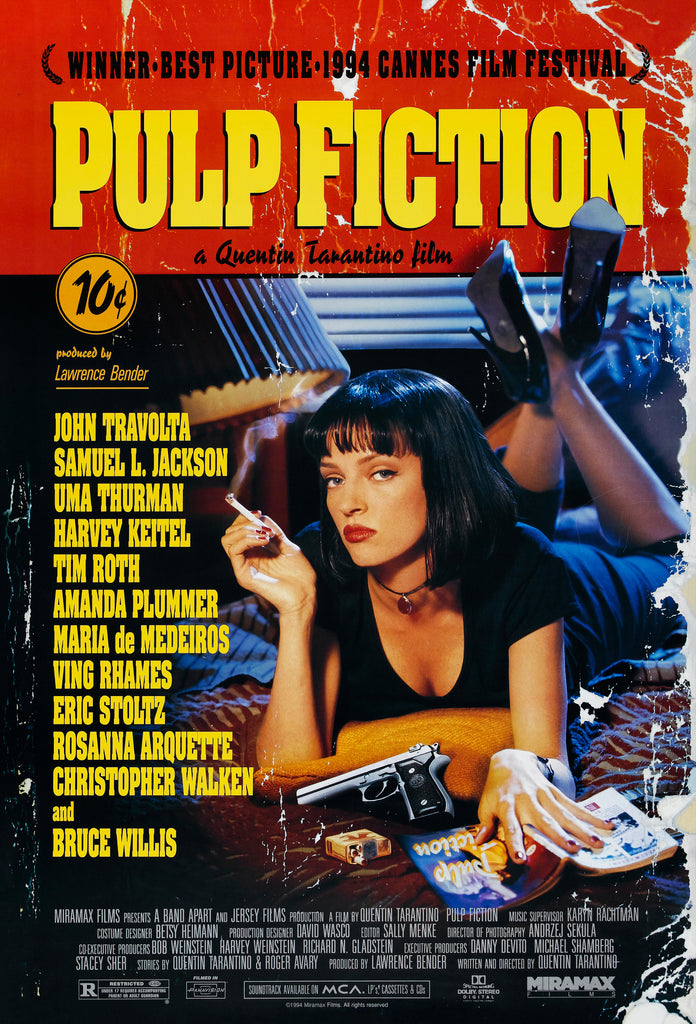

PULP FICTION (1994)

After the breakout success of Reservoir Dogs, everything suddenly seemed to bear Tarantino’s fingerprints. He sold screenplays for True Romance and Natural Born Killers, and From Dusk Till Dawn got dusted off once he and Rodriguez were hot property.

Then there was the small matter of his second film. If the exact meaning of what Reservoir Dogs refers to still causes some debate, the title of Pulp Fiction felt like a mission statement. Emboldened by the success of his debut and with a larger budget and even more eclectic cast to play with, Tarantino was here to celebrate the twists, turns, badass characters, and snappy dialogue of the crime movies and exploitation flicks he loved when he was growing up.

As I’m sure I’ve already said on the blog, Pulp Fiction was a movie I couldn’t wait to see again from the opening licks of Dick Dale’s “Misirlou” over the opening credits. Even more confident and polished than its predecessor, Tarantino took us on the wild ride through the back streets of LA, delighting in wrongfooting us with strange plot turns along the way. It featured many stock characters from crime fiction, including mob bosses, hit men, and a femme fatale, but mashed them together in wholly unexpected ways.

Tarantino’s specific ear for dialogue was key to the film’s success: Assassins discussed burgers before carrying out a hit, while Christopher Walken popped up for a monologue about hiding a valued heirloom up his ass. Casting was another strong point, and would become a notable feature throughout Tarantino’s filmography. In Pulp Fiction, the big news was the resurrection of John Travolta, who had languished in the ‘80s and was all but washed up before Tarantino came calling. Travolta’s addled performance earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Actor, while the equally eye-catching Samuel L. Jackson was deservedly nominated for Best Supporting Actor.

Pulp Fiction won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and was also nominated for Best Picture at the Oscars. Tarantino also received a nod for Best Director, but the Academy wasn't quite ready to give him and his violent tale of mysterious McGuffins, diner hold-ups, gimps, and barefoot dance-offs the big prizes. The far more conservative Forrest Gump and its director Robert Zemeckis went home with the little golden fellas instead. No matter; Tarantino was well and truly in the big time, and could now make just about any movie he wanted. And so he did, for the rest of his career to date.

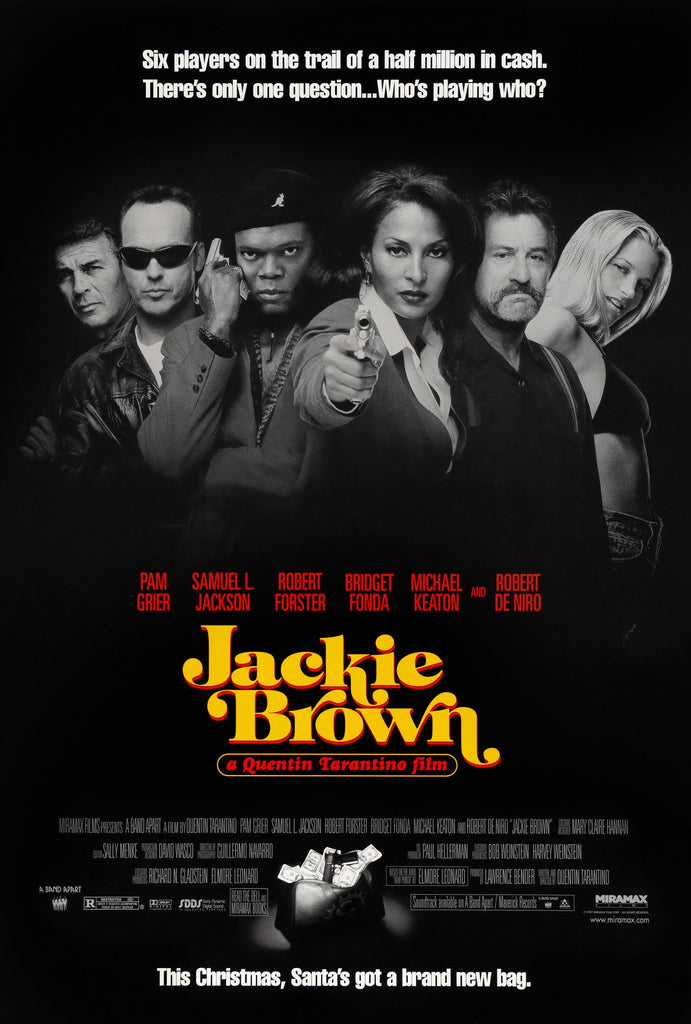

JACKIE BROWN (1997)

After the dizzying success of Pulp Fiction, what could Tarantino possibly do to top it? Perhaps wisely, he chose a change in pace and tone altogether. Instead of an original screenplay, Tarantino adapted Elmore Leonard’s novel, Rum Punch, and the resulting film was a far more soulful and lowkey affair. After the pure adrenaline burst of Pulp Fiction, I remember feeling rather restless and a little disappointed on my first viewing of Jackie Brown. Sure, it had great performances, a few quotable lines, and some stylistic flourishes, but it felt disorientingly like just a regular movie.

The key talking point in the run-up to its release was the casting of Pam Grier in the lead role. She was already a cult legend after her sassy, ass-kicking roles in a string of Blaxploitation classics in the ‘70s, but her career was even deader than Travolta’s before Pulp Fiction. Would she have the chops to carry the film?

The answer was a resounding yes. She perfectly embodied Jackie’s uncertainty and world-weariness as a woman in her mid-40s with very few options, earning a meagre paycheck as an airline stewardess who is drawn into smuggling for a lowlife gunrunner, played with pure malevolence by Samuel L. Jackson.

Tarantino paired Grier with Robert Forster, another old face whose career had flatlined years before, who played bail bondsman Max Cherry with an understated authority and decades of sadness and disappointment behind his eyes.

The relationship between Jackie and Max is the heart and soul of the film, and it’s the reason I come back to Jackie Brown more than any other Tarantino movie. It may not be as funny, stylish, or thrilling as his other stuff, but it is something of an outlier in his career; a grown-up story about recognisably real people, with tangible regrets and tentative hopes for a better future.

KILL BILL Volumes 1 & 2 (2003, 2004)

Six years passed before Tarantino returned with his most audacious project yet. Returning to the seamy world of professional killers, the director this time paid homage to ‘70s kung fu and samurai films, with a particular debt of gratitude to Lady Snowblood.

Taking us even deeper into the Tarantinoverse than ever before, the Kill Bill movies gave Uma Thurman a meaty signature role as The Bride, a retired assassin hellbent on vengeance after her former lover and employer tried to have her whacked on her wedding day.

Released two years apart, the double volume makes up one film in Tarantino’s catalogue, and he took a big risk putting most of the action in the first part while reserving most of the characters’ soul-searching in the slower, talkier, more contemplative second instalment.

It’s a gambit that works better with repeat viewings, and the action sequences throughout are astonishing. Thurman embodies the Bride physically and emotionally, and she really looks the part as she lays waste to scores of goons with her samurai sword or takes on Daryl Hannah in a bone-crunching trailer punch-up. The streamlined revenge plot keeps both movies rattling along towards the final showdown even as we take various diversions, such as a bravura anime sequence and a training montage that gives a heavy wink to Shaw Brothers flicks. In short, Kill Bill is a double bill that only Tarantino could get away with and pull off so successfully.

DEATH PROOF (2007)

Death Proof is a strange beast, and widely regarded as Tarantino’s weakest film to date. That said, Tarantino misfiring is still better than most cineplex hacks working at 110%, and it’s definitely not without its strong points.

Delving even deeper into his love for exploitation cinema, Death Proof draws on everything from Vanishing Point to Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! As a trio of feisty friends go up against a serial killer who uses his car as a murder weapon. If nothing else, the movie should be celebrated for being the first film in Kurt Russell’s renaissance, and he eats up the screen as the charming but sinister Stuntman Mike.

Where the film falls down is in the rest of the casting and the writing. The three protagonists are pretty generic and they don’t have the same kind of panache with Tarantino’s dialogue, which simply isn’t as sharp this time around anyway. This means long stretches of bland blather between Kurt doing his thing before we get to the high-octane finale, which is easily Tarantino's greatest action sequence so far. With real actors dangling off real muscle cars on real roads, it is real heart-in-the-mouth stuff.

Although Death Proof was released as a standalone feature, it was conceived as a double-bill called Grindhouse, paired with Robert Rodriguez’s equally uneven Planet Terror. A notable feature of the project was a series of trailers for fictional movies including Machete, which became its own spinoff franchise, and Don’t, directed by Edgar Wright.

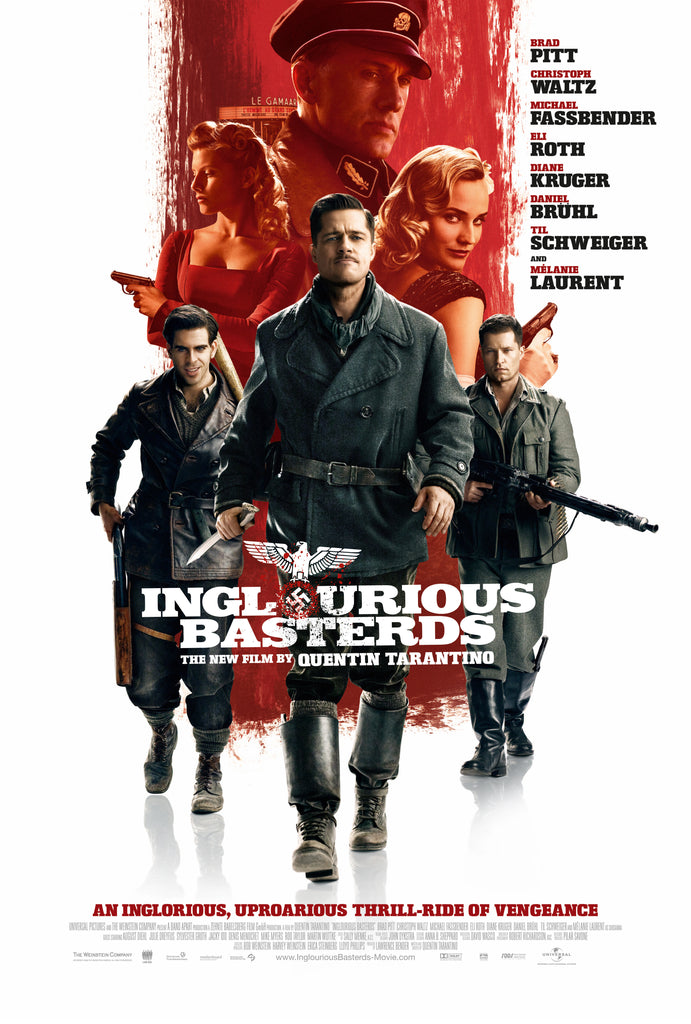

INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS (2009)

Those Nazis, huh? Don’t you just wish someone could kill Hitler and his cronies and make everything right? That’s where we ended up with Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino’s first venture into retroactively taking revenge for past atrocities. He spent around a decade working on the script, which he declared his “guys on a mission” movie like The Dirty Dozen and Where Eagles Dare.

Inglourious Basterds has guys on a mission, with Brad Pitt and his maverick gang of Jewish commandos working behind enemy lines before receiving a suicide mission to take down Hitler and the hierarchy of the Third Reich. Yet while Pitt's superstar presence played a prominent part in the marketing campaign, he is very much a supporting character.

Instead, the bulk of the film focuses of Colonel Hans Landa, a.k.a. The Jew Hunter, and his pursuit of a young girl who got away from one of his massacres. Both parts were played by virtual unknowns, Christoph Waltz and Melanie Laurent.

Once again, the casting was inspired. Tarantino originally wanted Leonardo DiCaprio for the part of Landa, but feared the role might be unplayable for a big-name actor. German-speaking Waltz stepped in instead, and he is absolutely captivating in the part. Landa is charming, erudite, relentless, corruptible, and utterly ruthless. The opening scene - as much influenced by Sergio Leone as any war movie - is one of the high points of Tarantino’s career, an exercise in sheer suspense punctuated by unlikely comic moments as Landa interrogates a French farmer suspected of harbouring a Jewish family.

While the film received a lengthy standing ovation at Cannes, Inglourious Basterds received some of the most vociferous criticism of Tarantino’s career, with Christopher Hitchens saying it was “like sitting in the dark having a great pot of warm piss emptied very slowly over your head.” Perhaps understably given the subject matter, members of the Jewish press weren’t exactly enthralled by Tarantino’s cartoonish revisionism, especially perturbed by how he effectively turned Jewish soldiers into Nazi-like executioners.

As a Brit whose grandparents fought in World War II I grew up laughing at the Nazis, from “Hitler has only got one ball” to Dad’s Army, and I can see the value of turning Hitler and his cronies into a figure of fun. That’s what Spielberg did in the Indiana Jones movies so successfully; by turning them into cartoon punch bags, he refused to give them the slightest bit of respect and robbed them of their power.

However, beyond the cathartic thrill of seeing a panto Fuhrer gunned down brutally, I’m not sure what Tarantino’s revisionism achieves. When Holocaust denial is on the rise and a startling percentage of young people don’t even know about the six million Jewish people murdered by Hitler’s regime, adding an extra layer of fantasy is potentially irresponsible. Thankfully, Tarantino lets Laurent’s Sossana have the final word.

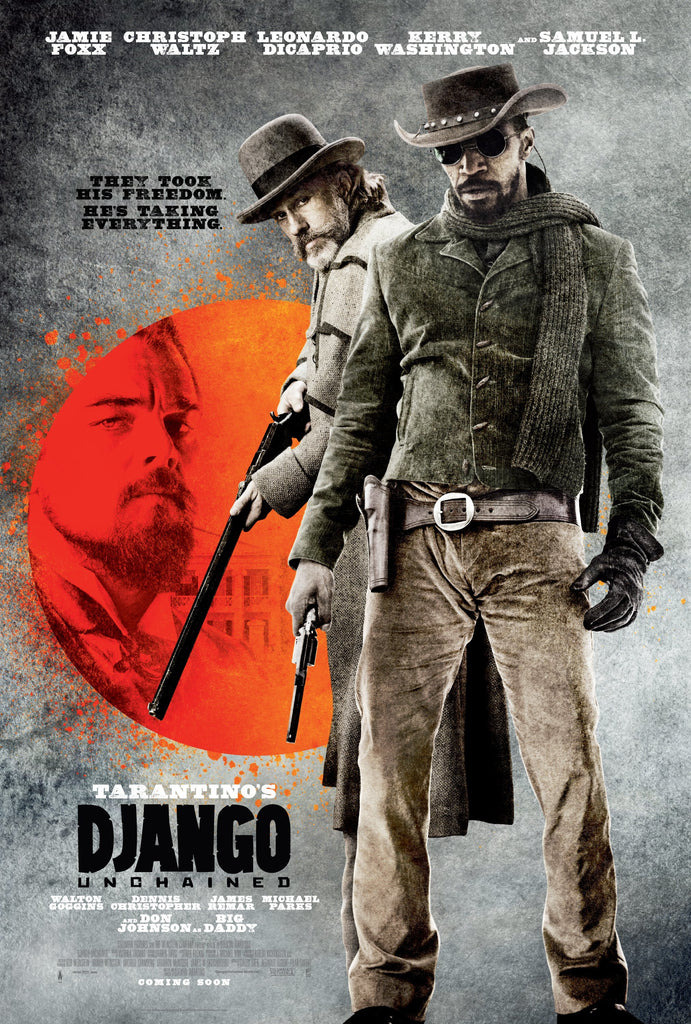

DJANGO UNCHAINED (2012)

With Hitler solved, Tarantino moved on to taking retribution for hundreds of years of slavery on behalf of African-Americans in Django Unchained, in the form of a blood-soaked spaghetti western.

He paid brief homage to Sergio Leone at the beginning of Inglourious Basterds, but this was the full monty, also borrowing key points from the lesser-known Sergio: Mr. Corbucci, who was a leaner, nastier version of Leone. Tarantino cribbed the title and the theme tune from Corbucci’s deranged masterpiece Django, but missed a trick by not stealing the original Django’s weapon of choice, a machine gun in a coffin.

Rambling in length and far patchier than Basterds, Django Unchained feels a bit aimless at times but still packs a punch where it counts. Released a year before Steve McQueen’s ponderous 12 Years a Slave, Tarantino’s revenge flick at least felt like it gave me a different perspective on racism and slavery. Samuel L. Jackson thought along similar lines, saying it was “a harder and more detailed exploration of the slavery experience” than McQueen’s Best Picture winner.

Predictably, Django Unchained provoked even more controversy than Basterds thanks to its extensive use of the N-word and depiction of slavery. Spike Lee was one of its most high-profile and vocal critics, stating he wouldn’t watch the film because it disrespected his ancestors: “American slavery was not a Sergio Leone spaghetti western. It was a Holocaust. My ancestors are slaves stolen from Africa. I will honor them.”

THE HATEFUL EIGHT (2015)

Inspired by the old TV western shows of his youth, The Hateful Eight sees Tarantino teetering on the brink of fatal self-indulgence. Surely only a director high on his own supply would shoot a three-hour movie in epic 70mm but set most of the action in a single interior location? Yet there was method in his madness; mixing western tropes with the snowbound paranoia of John Carpenter’s The Thing, the choice of format turns out to be an inspired decision when the drama really sets in. It’s a parlour mystery playing out like a stage play caught on film with little pockets of action and dialogue in various parts of the frame, giving it a real sense of claustrophobia and immediacy.

The daunting length might test the attention span of many, but rewards the patient. Tarantino’s wordy dialogue finds itself in service of an escalating series of murderous confrontations rather than yuks or the usual diversions. It’s like a tight 90-minute murder mystery thriller stretched out to such an extreme length that it’s in danger of snapping, but Tarantino is accomplished enough to play that dangerous tension for all it’s worth.

Like his previous two films, The Hateful Eight was not without controversy, culminating in on of the nastiest conclusions of any Tarantino movie. Some critics felt that the violent treatment of its tricky female protagonist, played with chaotic abandon by Jennifer Jason Leigh, was unduly harsh and bordered on pornographic. Others felt that it was in keeping with how real women would have been treated during that time.

Whichever side you land on, Leigh is magnificent, as is regular Tarantino collaborator Sam Jackson and a fully revived Kurt Russell sporting one hell of a moustache.

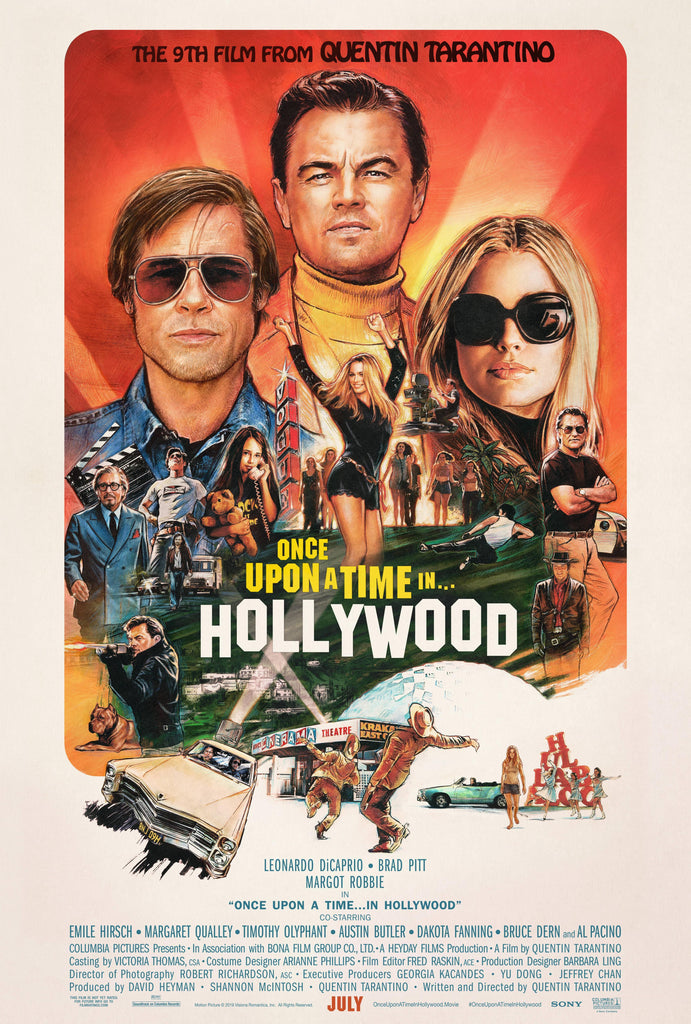

ONCE UPON A TIME... IN HOLLYWOOD (2019)

After the bleakness of The Hateful Eight, we arrive at Tarantino in his most freeform and benevolent. Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood is his most outright nostalgic film to date, lovingly recreating the Los Angeles of his childhood and often doing little else than driving around and enjoying the sun-kissed atmosphere. It’s a three-hour hangout movie that vibes on the love of old movies and TV shows, occasionally finding time to conclude Tarantino’s historical revisionism trilogy.

This time, he decides to rescue Sharon Tate from her murder at the hands of Manson Family. In doing so, he also rescues her from her previous status as a grisly footnote of Hollywood lore, so while the stakes are far lower this time around, Tarantino’s revisionism feels rather sweet when put to this use. Margot Robbie plays Tate as a carefree young actor on the cusp of becoming a star in her own right and she’s great in the part. She only has a few lines but she makes her feel so warm and full of life.

Of course, being a Tarantino movie, this means the Mansons need to die horribly and he doesn’t disappoint in a brutal finale that trades in shocked laughter as the Family members invade the wrong house, belonging to Leo DiCaprio’s struggling actor Rick Dalton and his laconic stuntman Cliff Booth, played horizontally laid back by Brad Pitt. Their chemistry is just perfect.

So there you have it, Tarantino’s nine films to date. What is your favourite? What do you think he will do for his tenth and final movie? Let us know!