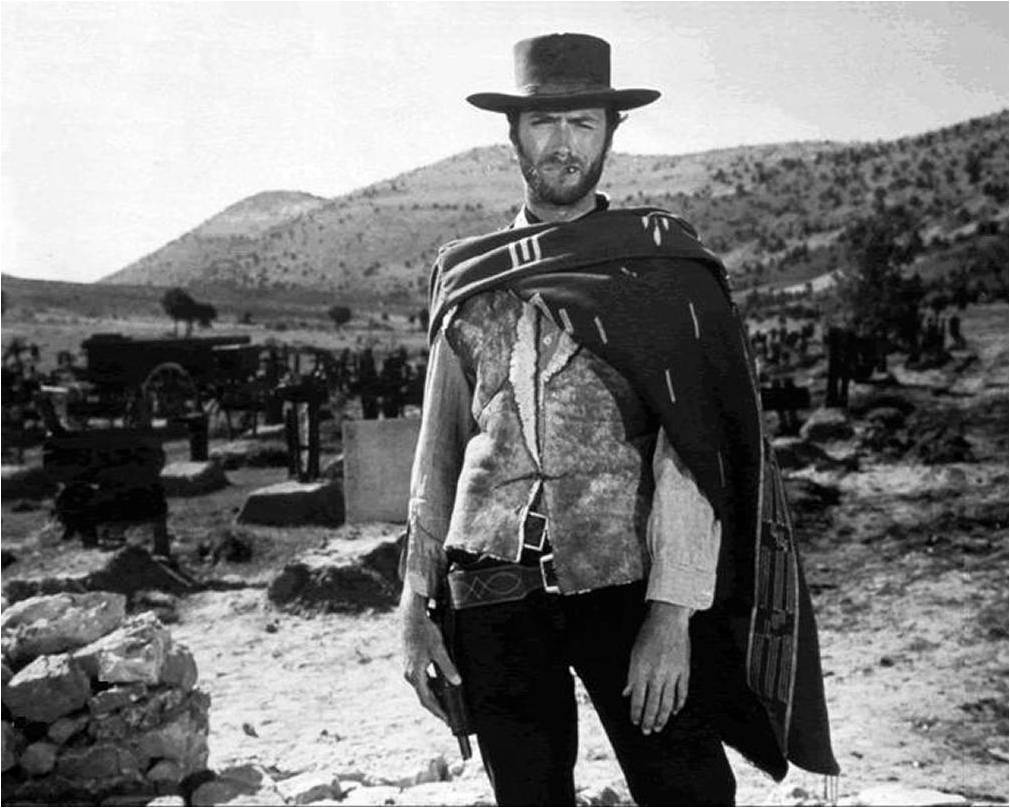

Westerns are one of cinema's oldest genres, but chances are that if you mention the word to a modern film buff, the image of Clint Eastwood in a poncho is probably the first thing that springs to mind. Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy, released in the mid-60s, remain three of the most popular examples around, reflected by The Good, The Bad, and the Ugly’s rarified spot at #10 in the IMDb Top 250. But why have these three films, made by an Italian director who hadn’t even visited the United States before, become a touchstone for this most American of genres?

The history of westerns dates back almost as far as the Old West and predates Hollywood. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) may be the most famous early example, with legends of people running in panic from the image of a locomotive chugging towards the screen and Martin Scorsese quoting it at the end of Goodfellas. The genre is even older still, with the first narrative film thought to be Kidnapping by Indians, a British short from 1899.

Since those formative years, the evolution of the Great American Genre has been a distinctly international affair, with three very different countries helping shape the next big leap: the United States, Japan, and Italy.

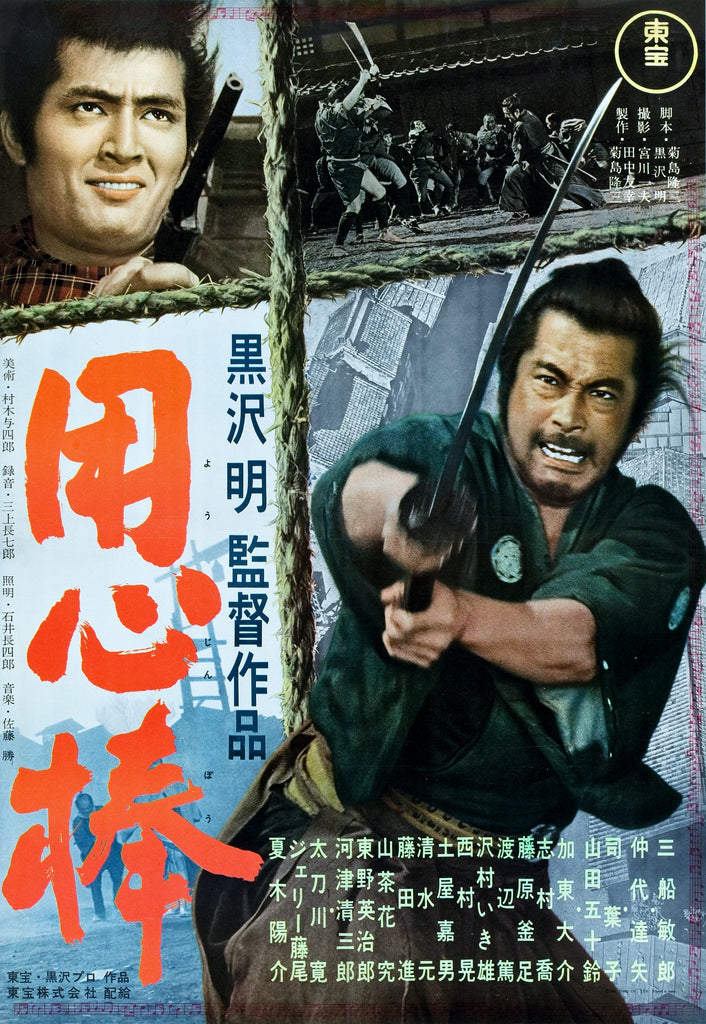

The basic timeline goes like this. John Ford mastered the Hollywood western from the 1920s to the 1940s and his films influenced a Japanese director called Akira Kurosawa. In turn, Kurosawa made some classic samurai movies with distinctly western-style narratives. Two of his best, Yojimbo and Seven Samurai, contributed to the next evolutionary stage. The latter was the template for John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven (not to mention Three Amigos! and A Bug’s Life) while Yojimbo inspired a young Italian director to make his own version.

Akira Kurosawa's Yojimbo

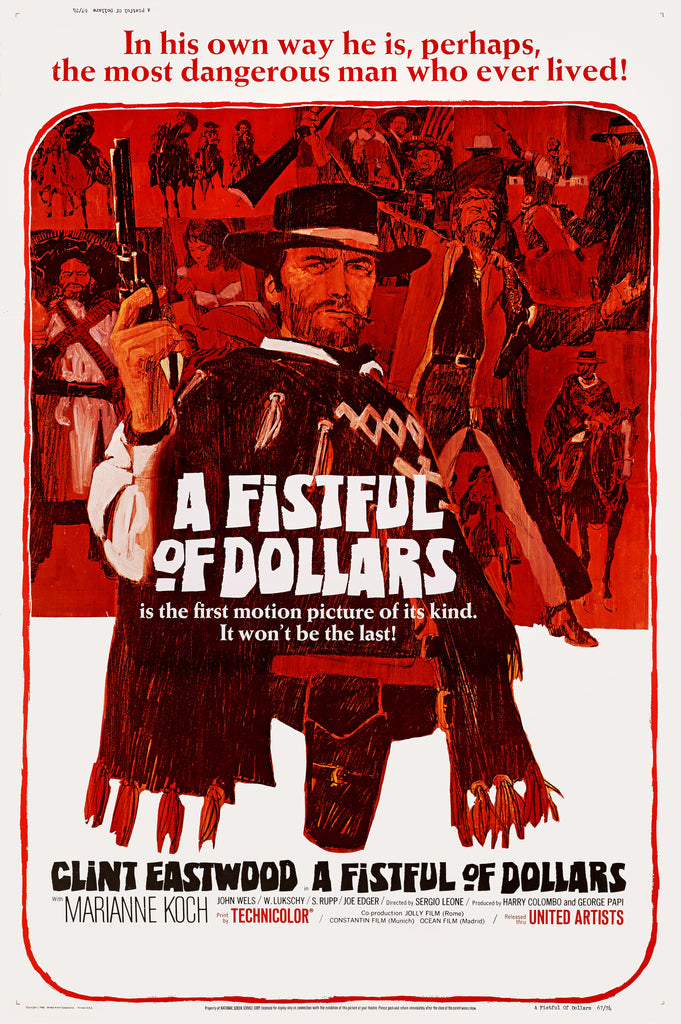

Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars shamelessly ripped off Yojimbo and Toho studios successfully filed a lawsuit that delayed its release in the States for three years. Yet while the story follows Kurosawa’s almost beat-for-beat, the style was very much Leone’s own and he developed it further in For a Few Dollars More; The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, and a fourth film, Once Upon a Time in the West. The first three of this quartet became known as the Dollars Trilogy, launching Clint Eastwood to international stardom and popularising the Spaghetti Western.

Leone’s distinctive take on the Old West would influence a darker, more fatalistic wave of American westerns by directors like Sam Peckinpah (The Wild Bunch), Robert Altman (McCabe & Mrs. Miller), and Eastwood himself, who would continue to explore his own role in the genre with High Plains Drifter, The Outlaw Josey Wales, and Pale Rider.

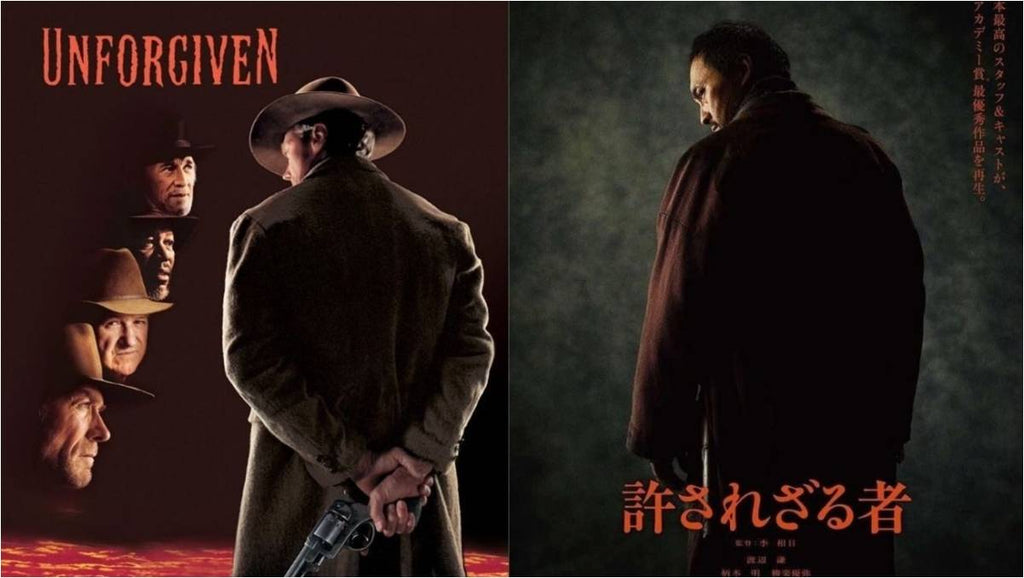

In the ‘80s, the Western was largely considered dead after the monumental flop of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, but it has proven an incredibly resilient genre. Kevin Costner kick-started it again with the critical and commercial success of his Oscar-winning Dances with Wolves before Clint Eastwood also won Best Picture with Unforgiven. While Costner’s epic is sometimes written off as a bloated vanity project, Eastwood’s film is one of the greatest westerns of all time, an unflinching examination of the “Man With No Name” persona he developed in the Dollars Trilogy.

To complete the cycle, Unforgiven was remade in Japan almost 20 years later with Ken Watanabe in the lead role, switching the setting back to the Samurai era. The poster even quoted the artwork for Eastwood’s film.

That’s a very brief overview (I didn’t even mention John Wayne!) but it gives an indication of how the western is more cosmopolitan than we might initially think. The iconography might originate in the Old West, but people from all over the world love playing cowboys and indians.

Out of this huge genre filled with so many classic films, it is Sergio Leone’s Dollars Trilogy that remains the most broadly popular. That’s if IMDb’s Top 250 is anything to go by: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly sits at #10 and you have to scroll all the way down to #52 to find another western, Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West. Incidentally, Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai clocks in at #22 and Django Unchained is at #56 – Tarantino has cited another Spaghetti western maestro, Sergio Corbucci, as a main source, but Leone was also a clear influence.

For a Few Dollars More is at #129, Unforgiven at #147, Yojimbo at #151, and you have to go all the way back to #239 before John Ford makes his first entry in the popular rankings – and that isn’t even a western, but rather his sterling adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath. Indeed, Ford may be revered as the father of the genre and has influenced a wide array of great directors including Kurosawa, Orson Welles, Federico Fellini, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, and Georg Lucas, but not a single one of his horse operas makes the IMDb Top 250. It just goes to show how viewer’s tastes have moved on since Ford passed away in 1973 and his iconic muse John Wayne hung up his six-shooter for eternity in 1979.

As regular readers of the blog will know, I love comparing the mainstream appeal of IMDb user’s choices with the highbrow picks of Sight & Sound voters, so for the sake of completeness let’s take a look at how that stacks up against the BFI’s once-in-a-decade poll. There, it is a different story: John Ford’s masterpiece The Searchers sits proudly at #15, Seven Samurai at #20, and you have to scroll all the way down to #95 before the first Sergio Leone entry, Once Upon a Time in the West. John Wayne gets another look-in at #101 with Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo, John Ford again with The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance at #108, and Leone gets his second mention at #157 with Once Upon a Time in America. The Dollars Trilogy finally receives acknowledgement at #169 with The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly. John Ford makes it a hat-trick of westerns at #243 with My Darling Clementine, but the rest of Leone’s trilogy are absent.

So what does that tell us about the contrasting virtues of John Ford and Sergio Leone, and why does the latter hold such an enduring place in popular culture? Let’s dig into it.

Sergio Leone was born in Rome in 1929 and studied law before he decided to switch careers to the film industry instead. He cut his teeth on Vittorio De Sica’s classic neo-realist fable Bicycle Thieves; writing swords-and-sandals movies; and paying his dues as Assistant Director on religious epics like Quo Vadis and Ben-Hur, both of which were shot at the vast Cinecittà Studios in his home city. He got his big break in making movies on The Last Days of Pompeii when the original director, Mario Bonnard, was taken ill and Leone stepped in to complete the picture.

His first full feature at the helm, The Colossus of Rhodes, gave little indication of the style that Leone would develop in his next film. The Italian didn’t speak English and had never visited the United States at that point, but he had been fascinated by the Old West since he was a kid and was very knowledgeable on the subject. So when he got a chance to make his own cowboy movie, Leone paid homage to the films he grew up with but completely changed the rules.

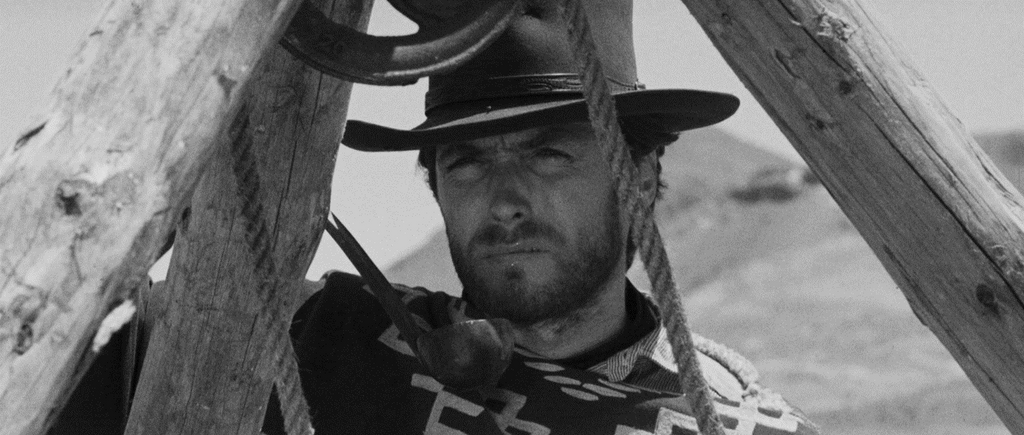

Leone’s vision was more gritty and morally ambivalent than the classic White Hats vs Black Hats narrative common in the Hollywood westerns of the ‘30s and ‘40s. This was typified by his protagonist in all three films. Whereas the heroes in Hollywood horse operas were often upstanding gunslingers with a keen sense of conscience, his “Man With No Name” was an anti-heroic drifter who wandered into each movie with a keen eye on making money ahead of what he could do for society.

Set in rustic villages against the stark sunbaked backdrop of Spanish hills and plains, Leone’s films were cool, cynical, ironic, an attitude matched by Clint Eastwood as the supposedly moniker-less focal point. In many ways, Eastwood’s iconic character was the first modern action hero, a sharp-shooter with a fine way of delivering killer kiss-off lines, a precursor for the likes of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sylvester Stallone, and Bruce Willis in the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Opposing Eastwood’s character(s) was a swarthy gallery of fascinating and often grotesque faces – unshaven, crooked, wonky-eyed, manky-toothed, sweaty, tobacco-spitting, leering, sneering villains whose unkempt features nevertheless looked magnificent in Leone’s trademark mega close-ups.

This stood in stark contrast to the type of actors who usually occupied the screen in Hollywood westerns; good or bad, they were usually bland and handsome. Leone’s ambivalent approach to his characters stemmed from his experience as a kid during World War Two, when he experienced real Americans for the first time. GIs were on the streets of Rome and they weren’t the clean-shaven heroes that a young Leone idolised in the Hollywood pictures imported and dubbed into Italian. Many of them were crude, drunken, ill-shaven skirt-chasers out for what they could get as the conflict came to a close.

This informed Leone’s approach to westerns, which had largely been romanticised by the films of John Ford, Anthony Mann, Howard Hawks, and populated by upstanding straight-shooters like John Wayne, Henry Fonda, and Gary Cooper. The Old West, Leone knew, was a raw and unforgiving place forged by tough characters ranging across the entire moral spectrum, and the intentions and actions of those pioneers certainly weren’t always informed by an unwavering sense of good conscience. This was the central thesis of his spaghetti westerns, and his leading man and composer would help complete a vision that would transform the genre to this day.

Clint Eastwood was already well into his 30s when he landed the role that would make him a household name all over the world. In the early ‘50s he spent a few years in the US Army and briefly worked at a gas station before trying his hand at acting, playing bit-part roles and making his screen debut in Revenge of the Creature, the sequel to the hit monster movie Creature from the Black Lagoon. He made ends meet building swimming pools and driving a garbage truck before he got the break that brought him to national attention, playing Rowdy Yates in the popular western TV show Rawhide.

Although Eastwood was now on the radar in the genre, he was far from Leone’s first choice when it came to casting the lead in A Fistful of Dollars. The director originally wanted his idol Henry Fonda, but he was too expensive. His next choice, Charles Bronson, rejected the part because he thought the script sucked. Several other lesser-known actors were approached including Rory Calhoun, Steve Reeves, and Richard Harrison, who had appeared in another Italian western called Gringo. Harrison hadn’t enjoyed his experience on that film and also turned Leone down, but he still made his mark: He recommended Clint Eastwood. Harrison later joked that it was his greatest contribution to cinema.

Leone decided that Eastwood was exactly what he was looking for and saw the American’s relatively limited range as a bonus rather than a flaw – memorably, the director said that Eastwood had two expressions, “with hat and no hat.” Eastwood helped develop the persona, coming up with the idea of the poncho and insisting on scratching out lines from the script to make himself more mysterious. The result was an archetype who was laconic, steely-eyed, and morally ambiguous, although one possessing a skewed sense of justice. Eastwood’s features, now pleasantly weathered with a little age, also looked incredible in widescreen.

The Man With No Name bit came later, a marketing ploy cooked up after the event by United Artists to sell the movies to an American audience. Leone didn’t intend for the three films to form a trilogy and it isn’t clear whether Eastwood is supposed to be playing the same character throughout. Although he wears the same outfit and carries himself with the same mannerisms, he has a different nickname in each: Joe in A Fistful of Dollars, Manco in For a Few Dollars More, and Blondie in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.

To add to the minor confusion, other actors appear in more than one film in the trilogy playing different characters, most notably Lee Van Cleef and Gian Maria Volonte. Furthermore, the films aren’t a trilogy in the traditional sense as they are not connected narratively, and the last can be seen as a prequel because it is set during the American Civil War. Whichever way you look at it, Eastwood’s presence on screen provided the connective tissue between the three films, along with the innovative music of Ennio Morricone.

![]()

Leone and Morricone went way back. They were in third grade together as kids but lost contact until the director came calling years later, asking Morricone to soundtrack his new picture. Leone intended the music to be a big part of the film from the start, and some of the score was written before cameras even rolled. The composer later said that Leone let some scenes carry on to fit the length of the tune, resulting in the film’s relatively languid pace.

Another key contributor was Edda Dell’Orso, the Italian singer who provided the whistling and vocals on the soundtrack. She would return and give her invaluable contribution to the next two pictures, too. With the possible exception of Steven Spielberg and John Williams, Alfred Hitchcock and Bernard Hermann, Leone and Morricone formed perhaps the most memorable and symbiotic director-composer partnership ever.

Sergio Leone’s Spaghetti Westerns were made roughly equidistant between the origins of the genre and the present day, and it’s hard to think of another example of a series of films that so definitively drew a line under what came before and set the tone for everything that came after. Perhaps that is why the Dollars Trilogy remains so popular today.

While many directors cite John Ford as a major influence and critics still adore his work, Ford’s films appear dated to the modern eye, not helped by the problematic presence of John Wayne. Even early Revisionist Westerns that were starting to examine the tropes of the genre like High Noon (1952), Johnny Guitar (1954) and Ford’s The Searchers (1956) all have elements that root their style firmly in the Golden Age of Hollywood westerns.

By contrast, Leone’s Trilogy has a more modern sensibility and its visual language still influences the way films are made today. Even 60 years on, there is little to date them. They still feel fresh and dynamic, in large part thanks to the combo of Eastwood’s wry performances, Leone’s bravura stylistic choices, and Morricone’s innovative music, which calls attention to itself as a key component from the get-go. It also helps that shooting the films on location in Spain and using character actors that were so unconventional in appearance gave the films a completely different look, one grounded in hot and sweaty reality despite Leone’s operatic approach to his episodic tales of greed, violence, and revenge.

For a director with such a towering position in cinema, it’s easy to forget that Sergio Leone only made a handful (or fistful) of films in his career. It’s fascinating to watch how his direction and themes evolve throughout the trilogy while maintaining a consistent tone. A Fistful of Dollars is little more than a cool calling card where Leone establishes his game-changing style.

For a Few Dollars More ups the stakes by adding a second main character competing with Eastwood’s for the head of El Indio, Colonel Douglas Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef). Indeed, Manco is often relegated to the position of referee as the main thrust of the story is Mortimer’s quest for revenge against the maniac who raped and killed his sister years earlier. The film is still a rollicking good time with Leone further exploring the endless possibilities of the showdown and Morricone having a blast with the score, but the overall tone is mournful, making it the most emotionally impactful film of the series.

Leone broadened the scope even further with The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly by setting the action against a backdrop of the American Civil War, a human tragedy that makes the naked greed of the three main characters feel particularly grubby and nihilistic by contrast. Once again Leone concludes with a ground-breaking showdown, this time between three competing treasure hunters in a Confederate graveyard to claim the loot.

The showdown is a trope of the western genre as common as cowboy hats and batwing doors on saloons, and arguably no-one has done it better than Leone. He was fascinated by the dramatic possibilities of those endless few seconds before the moment of crisis, when the duelists draw their pistols and try to shoot each other dead in a brief flurry of violence. It is in these scenes that Leone’s style comes to the fore, those huge close-ups registering every flicker of the eye and twitch of the lips as Morricone’s score cranks up the tension.

Once the Dollars Trilogy was complete, Leone wanted to move away from westerns completely towards another very American genre, the gangster film. He had come across Harry Grey’s The Hoods, an epic tale of Jewish mobsters during the Prohibition Era, and intended it to be his next project. United Artists tempted him with a boatload of money, however, and the chance to work with his idol, Henry Fonda, to stay in the Old West.

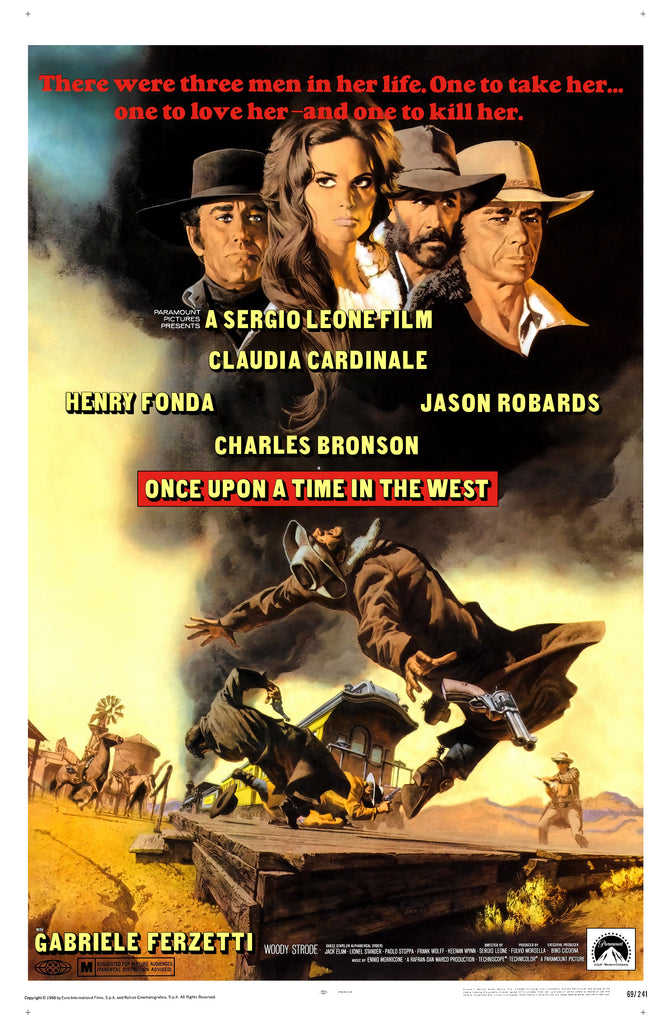

The result was Once Upon a Time in the West, with Fonda playing against type as a dead-eyed killer working for a railway tycoon. Clint Eastwood turned down the lead, giving Leone the opportunity to cast another of his earlier picks, Charles Bronson. Opening with perhaps Leone’s greatest shootout and stretching almost three hours, the film was the director’s elegy for the Old West, pitching Frank (Fonda), Harmonica (Bronson) and a third gunslinger, Cheyenne (Jason Robards) as relics of a way of life that was becoming extinct as the railroad brought civilisation and modernity to the frontier.

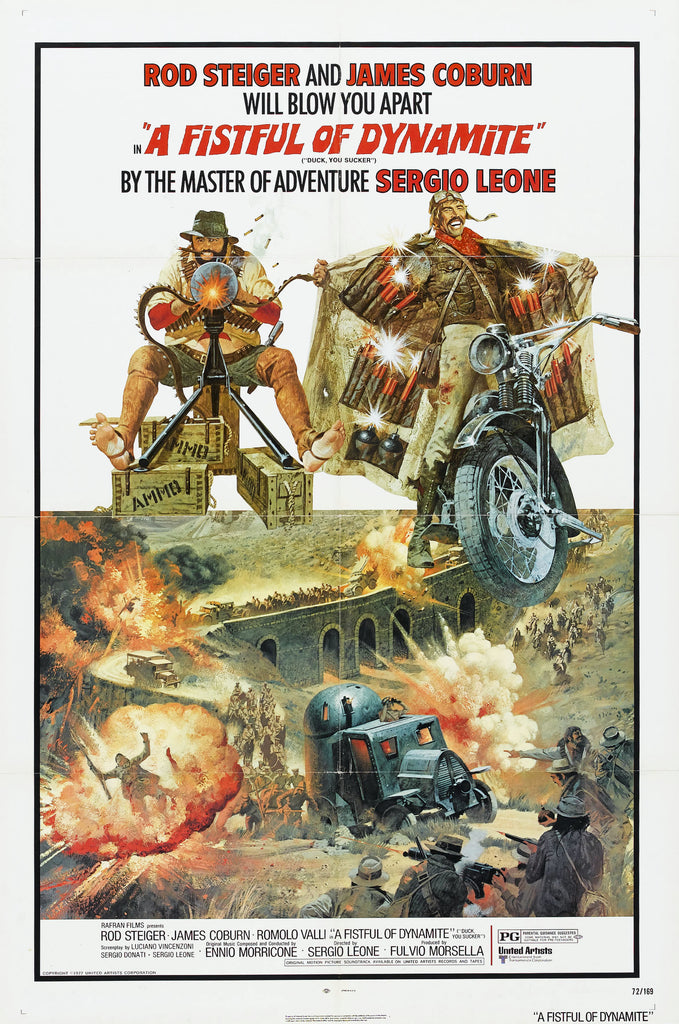

Leone still had one more western in him, the lesser-seen and only half-successful Duck, You Sucker! (aka A Fistful of Dynamite), before he finally realised his dream of adapting The Hoods as Once Upon a Time in America. Its gargantuan running time was brutally cut down by the studio and was a critical and commercial failure. Sadly, it was Leone’s final film and his death in 1989 meant that he passed away before it received reappraisal as a gangster masterpiece.

Sergio Leone was one of the greats, a true stylist and visionary who changed the face of cinema in just seven films. Of them, the Dollars Trilogy will no doubt endure as three of the most popular westerns ever made, ensuring that Leone's influential legacy lives on.

So there you have it, our retrospective on the Dollars Trilogy. What is your favourite of the three movies? Let us know!