The ‘90s was a great decade to start a serious love affair with film. As I’ve no doubt said elsewhere on the blog before, the trio of Pulp Fiction, Trainspotting, and Seven were the films that really made me understand that there was somebody behind the camera making decisions about how the movie turned out on the screen.

That might sound obvious, and of course I knew movies didn’t just appear fully formed out of the ether, but my appreciation for cinema just went to another level once that concept and all it entailed really clicked in my head.

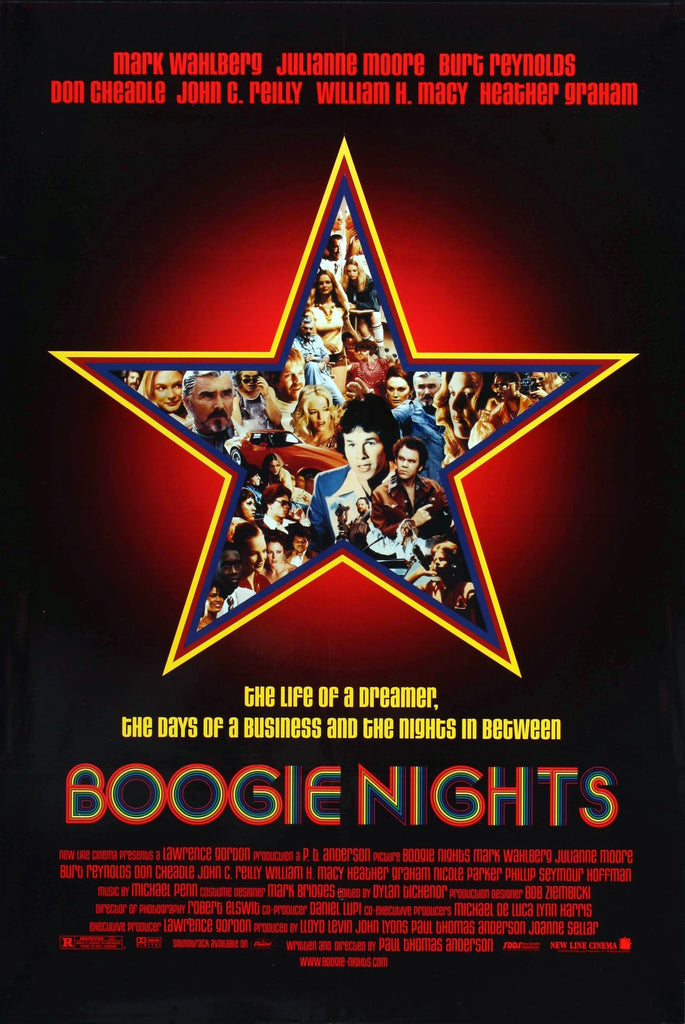

Then came Boogie Nights. I remember seeing it at the cinema for the first time and walking home afterwards, so totally jazzed by the filmmaking that I felt like I was strutting along like John Travolta at the start of Saturday Night Fever. Paul Thomas Anderson was obviously a serious new talent and I couldn’t wait to see what he’d do next.

That has become the recurring theme of watching PTA movies. As we’ve found out, you never know what he’s going to do next, and he has yet to make two films alike, jumping from era to era and shifting in tone from serious drama to stoner comedy.

With nine films to date, Anderson now has the same amount of movies as Tarantino, another of the “video store’ directors who came to prominence in the ‘90s. They are both movie magpies, although in a different way. While QT pays homage to his favourites by putting his own spin on his favourite bits of old movies, Anderson borrows more from the style of other directors, most notably Martin Scorsese and Robert Altman. Yet while he wears his cinematic influences on his sleeve, the feel of a PTA movie is wholly unique, making him one of the most exciting American auteurs of the past 30 years.

Like Tarantino, the prospect of a new PTA film has movie buffs clearing a date on their calendar for opening night. Let’s take a look at his idiosyncratic, totally singular career so far…

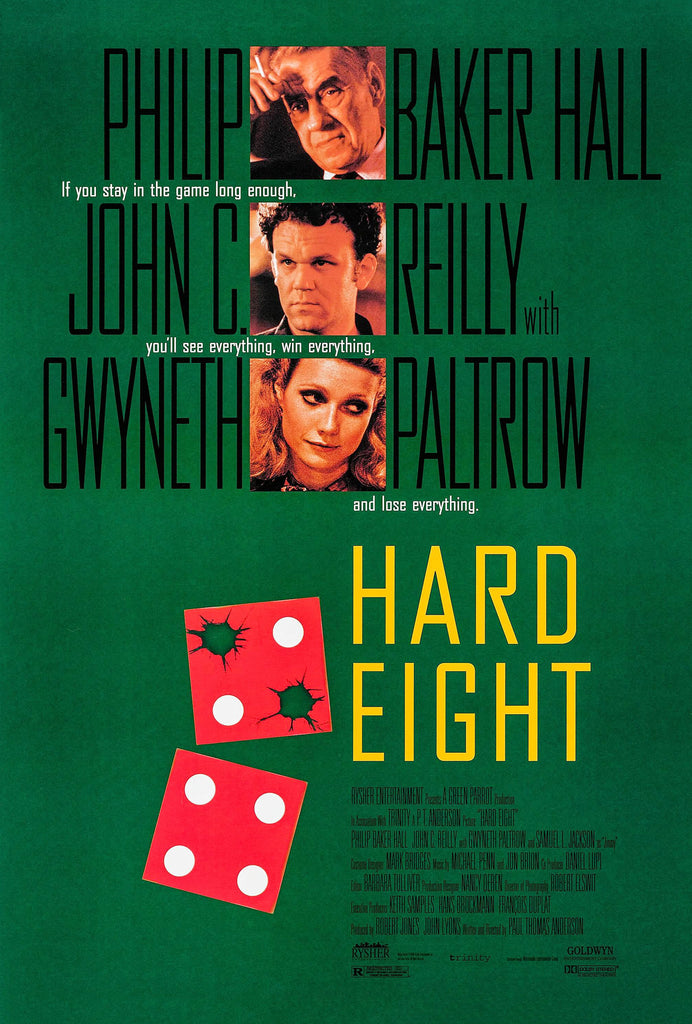

Hard Eight (1996)

Often directorial debuts can look a little rough around the edges but Anderson’s elegant, confident style was evident from the very beginning. Hard Eight is one of the most accomplished calling cards you could wish to see, taking us deep into the world of low-level gambling. John Finnegan (John C. Reilly) is down-and-out after a ruinous trip to Vegas, but he is approached by Sydney (Philip Baker Hall), a gentlemanly professional gambler who takes him under his wing and shows him a few tricks of the trade.

Hard Eight was expanded from Anderson’s short film Cigarettes & Coffee which was a very ‘90s indie production, paid for with Anderson’s gambling winnings, college fund, and his girlfriend’s credit card. Crucially, he managed to get a seasoned actor like Baker Hall onboard and the short became a sensation on the festival circuit, enabling the director to develop it into his debut feature.

The film works best in the opening third as John and Sydney get to know each other and form a tentative partnership, giving us a fascinating glimpse into the lives of people who make gambling their livelihood. It only falters when Anderson feels the need to introduce a thriller element, which makes the film feel more generic as it meanders towards its conclusion.

Even so, it was a bold and stylish way for Anderson to kick off his career, working with a committed cast who are all on top form. Reilly has a harder edge here in the amiable doofus role we would become familiar with, while Gwyneth Paltrow, playing a forlorn cocktail waitress who turns tricks on the side, gives an open and unguarded performance that offers a reminder of why she was such a big deal in the ‘90s.

Samuel L. Jackson, playing John’s shady friend Jimmy, displays the same laidback menace he used to such great effect for Tarantino in Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown, but best of the bunch is Baker Hall as the mysterious, plain-spoken Sydney, a solitary man who has made the environs of neon-lit casino floors and comped hotel rooms his natural habitat. If this movie was further along in Anderson’s career, the veteran actor probably would have been looking at an Oscar nomination for the performance.

Boogie Nights (1997)

For his real breakout, Anderson again returned to one of his previous short films. At college he had created a mockumentary called The Dirk Diggler Story, charting the rise and fall of a young porn star. The result was Boogie Nights, which remains Anderson’s most purely entertaining movie to date.

Paying a clear debt of gratitude to Scorsese and Goodfellas, the first half of the movie takes us on an exhilarating ride into the world of adult film stars in the ‘70s, following the very well-endowed busboy Eddie Adams (Mark Wahlberg) who is discovered by porno impresario Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds) and turned into one of the biggest names in the business.

With virtuoso Steadicam tracking shots, fabulous fashions, endearing performances, and a killer soundtrack, the early stages of Boogie Nights is an absolute blast. Eddie, going under the screen name Dirk Diggler, meets a wide range of colourful characters including Rollergirl (Heather Graham), new best pal Reed Rothchild (John C. Reilly), and motherly Amber Waves (Julianne Moore), all of whom become a surrogate family to the newcomer with big ambitions.

If we’re being picky, Anderson doesn’t add much to the standard American Dream rise-and-fall story, and the contentious scene where we finally get to see what Eddie has tucked away trousers plays like an explicit callback to the final moments of Raging Bull. As with Hard Eight, Anderson also miscalculates by adding a needless thriller element when Dirk gets hooked on drugs and tries to rob a wacky dealer, a scene that feels like it wandered in from one of the many Tarantino rip-offs of the time.

Those mis-steps aside, Boogie Nights showed that Anderson was the real deal, a filmmaker who not only was extremely assured with the technical aspects but also a proper actor’s director. He brought out memorable performances from his entire cast, most notably turning Mark “Marky Mark” Wahlberg into an actor of real substance and getting the best from Burt Reynolds, whose career had languished since his ‘70s heyday.

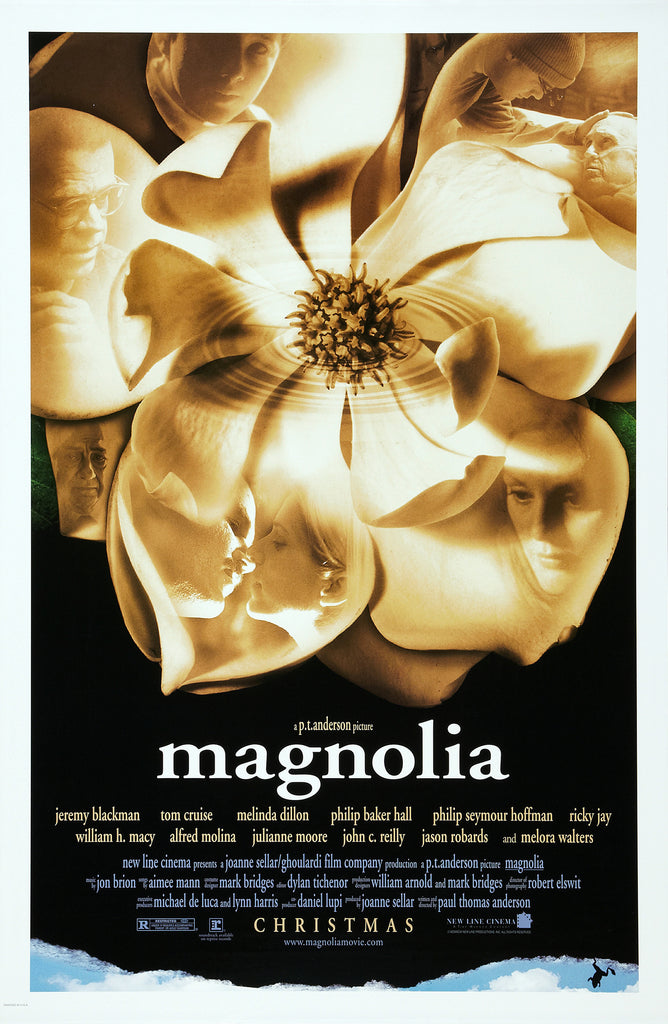

Magnolia (1999)

After channelling Scorsese in Boogie Nights, Anderson emulated Robert Altman with Magnolia, a sprawling ensemble piece that felt like an early victory lap just three films into his career. The film is ambitious in scope, charting the stories of several characters as they cope with loneliness, grief, disappointment, love, and try to make some sense of the seemingly random events that bring them together.

A less intrepid director might have been content to tell this kind of story in a traditional dramatic way, but Anderson had designs on making a grand statement on the coincidences that are threaded through all our lives, questioning whether some cosmic intervention is involved or just plain chance.

Like Scorsese, Anderson was already establishing a regular troupe of actors including John C. Reilly, Philip Seymour Hoffman, and Philip Baker Hall, and his rising star status also enabled him to add Tom Cruise to the mix, who was at his acting peak after a recent Oscar nomination for Jerry Maguire. Much was made of Cruise’s performance, also receiving a nod from the Academy as a toxic motivational speaker, but it is his portrayal that dates the movie now we have podcasts from Joe Rogan and the like.

Anderson goes big from the outset, opening his thesis with a flashy opening sequence that details three bizarre and tragic coincidences, and wraps it up with a sudden and unexpected cloudburst of raining frogs. Perhaps the theme doesn’t carry through the intervening three hours of drama as strongly as he might have intended, but Magnolia is certainly a bold statement.

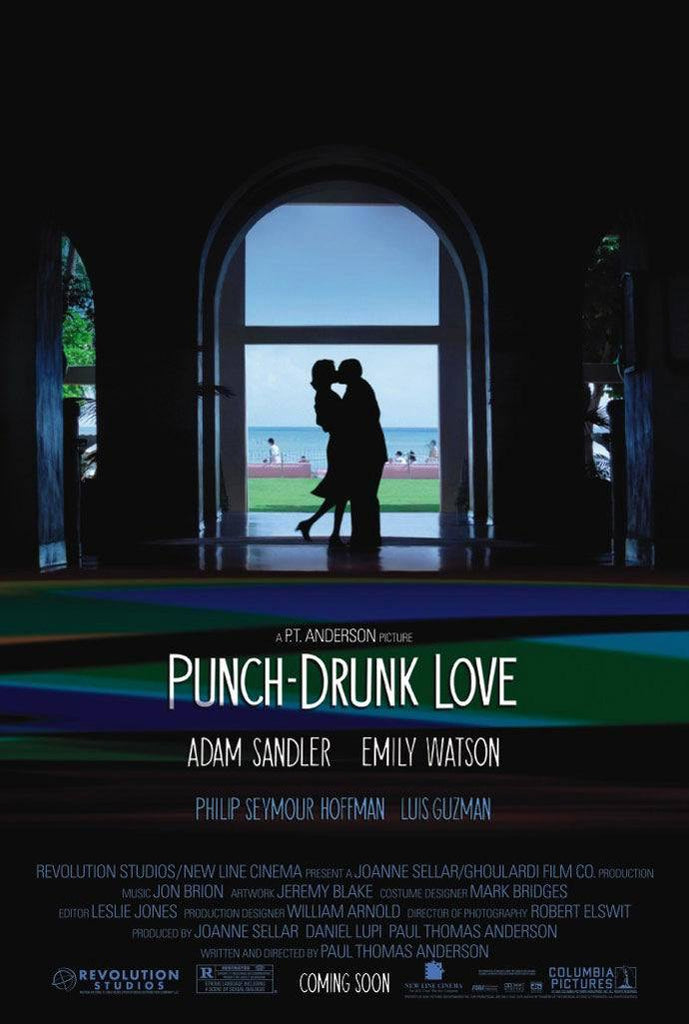

Punch-Drunk Love (2002)

Anderson hasn’t been shy about citing the many influences on his work, and he is similarly unabashed about his great love for Adam Sandler movies. On the strength of his opening hat trick of films, he got his wish to work with the actor on Punch-Drunk Love, initially causing some concern from his producer.

Anderson’s faith paid off. The much-maligned Sandler hinted at hidden depths to his usual shtick in The Wedding Singer, and he was well cast as Barry Egan, a lonely, socially awkward small businessman prone to violent outbursts. So far, so Sandler, but Roger Ebert astutely noted that Punch-Drunk Love was like PTA had “deconstructed the Adam Sandler movies and put them back together again at a different level.”

That’s a great way of describing the film’s offbeat rhythms, which are disconcerting in the early stages as Anderson puts us in the anxiety-ridden mindset of its protagonist. PTA is so successful in this aim that, I have to admit, it took me three attempts to make it through the movie. But taken in its entirety, Sandler’s surprisingly understated performance is full of ineffable sadness, which pays off once his unlikely romance with an awkward Brit expat (beautifully played by Emily Watson) finally comes together.

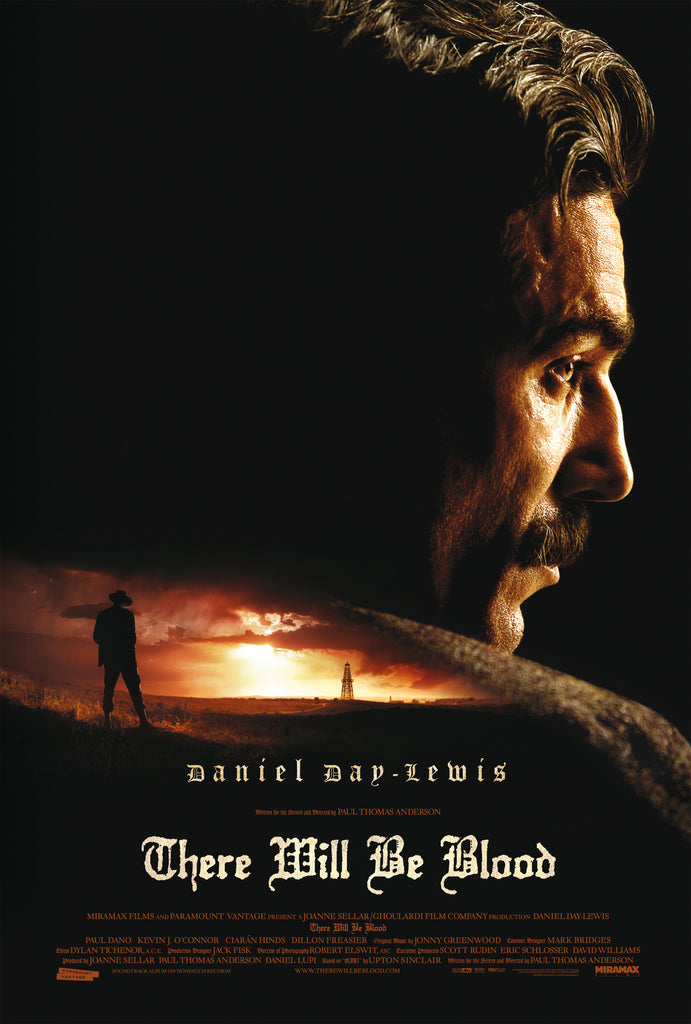

There Will Be Blood (2007)

From an understated performance by Adam Sandler, usually not noted for his subtlety, to a gloriously hammy turn from one of our greatest living actors, we arrive at There Will Be Blood. Daniel Day-Lewis is a full-blooded thesp who is at once familiar yet very distant and enigmatic, just as capable of marvellous nuance as he is not only chewing scenery, but gulping down massive chunks of a movie whole.

In that respect, his villainous performance as Bill the Butcher in Gangs of New York felt like something of a warm-up for his Oscar-winning performance as the monstrous oilman Daniel Plainview in Anderson’s black-hearted study of greed and the worst excesses of the American Dream.

There Will Be Blood made many critics’ lists of the best films of the Noughties, and it is perhaps PTA’s bleakest accomplishment to date. Shot with an unerring eye for period detail, it is a study in avarice, self-regard, and self-destruction, leaving us with our hearts in our mouths as we anticipate just how low this horrendous character can go.

The film is dominated by Day-Lewis’s gargantuan presence, but Paul Dano also edges his way into its litany of human corruption as twin brothers, one of whom will eventually lead to Plainview’s existential downfall.

It’s a grim, corrosive portrait, painstakingly detailing how the worst excesses of capitalism can consume an individual and turn them into a monster. For me, it is also a little one-note. Plainview is a terrible person when we meet him, he’s terrible all the way through the film, and he is even worse come the bizarre “drink your milkshake” bowling alley conclusion.

It isn’t much of a character arc and, as brilliant as Day-Lewis is, it is essentially a few hours spent staring into a tortured void where a human soul should be.

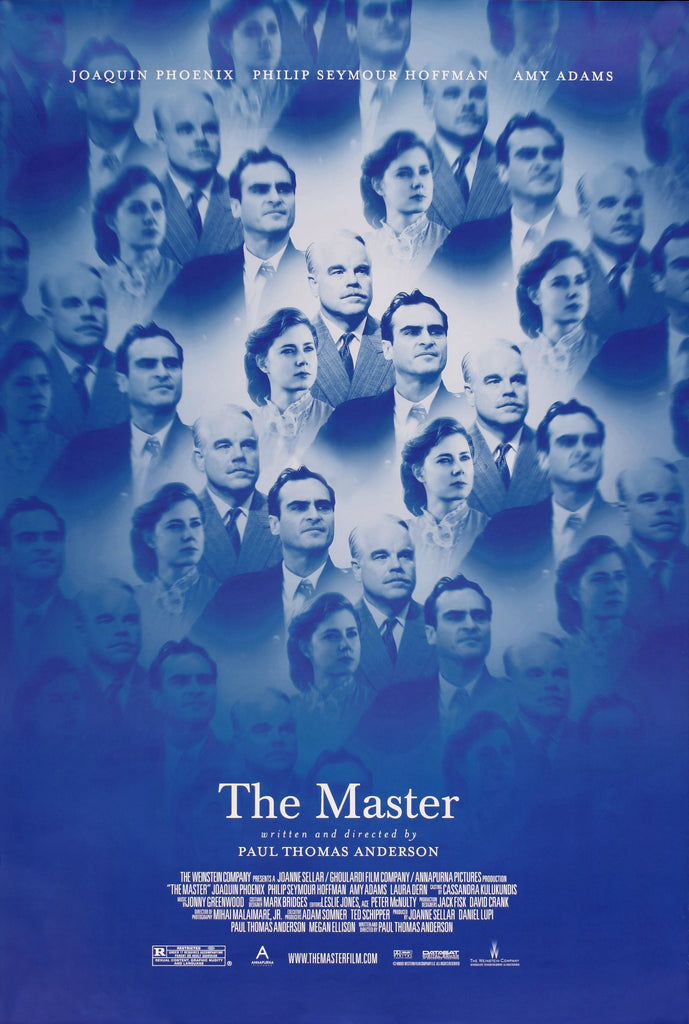

The Master (2012)

Philip Seymour Hoffman’s fifth and final collaboration with Anderson, coming just two years before the actor’s tragic death, was perhaps his best. Set in the period just after World War II, he plays Lancaster Dodd, the inscrutable but charismatic leader of a new Scientology-like movement known as The Cause.

It’s a strange, enigmatic film that has none of its predecessor’s single-minded obsession, becoming a gripping but elusive two-hander when Dodd encounters Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), a troubled veteran adrift in post-war normality. Dodd is fascinated by Freddie and he brings him into The Cause, to the consternation of his other acolytes. Dodd’s motivations are ambiguous. Does the egotistical cult leader see Freddie’s damaged soul as an enjoyable challenge compared to his sheep-like followers? What does he have to gain from having a combustible, potentially dangerous person like Freddie around?

Both Hoffman and Phoenix are superb in their roles, which the latter seemed to channel somewhat for his incredibly mannered performance in Joker. Here, Phoenix’s coiled anger and unpredictability give the film its edge, and his lengthy scenes with Hoffman are captivating. In some ways, their relationship reminded me of the psychological cat-and-mouse in John Fowles’ The Magus.

Needless to say, PTA’s filmmaking is absolutely immaculate. He always has a loving eye for period detail and his evocation of America in the immediate aftermath of such a momentous conflict is especially lovely.

Throughout his career Anderson has sought to break his narratives away from the traditional beats and The Master is specially hard to put your finger on, but the mercurial battle of wills at its heart offers plenty to viewers who like a bit of a challenge.

Inherent Vice (2014)

After his Oscar-nominated performance in The Master, Phoenix teamed up with Anderson again to play a very different type of protagonist in Inherent Vice. He plays Larry “Doc” Sportello, a herbally-altered hippie who somehow makes a living as a private investigator in ‘70s Los Angeles County. As is often the case for this kind of Chandleresque mystery, Doc starts out poking around in a seemingly simple case and gets drawn into a far larger conspiracy.

What that conspiracy is will remain elusive to all but the most attentive viewer, as the plot of Inherent Vice is labyrinthine by even the usual standards of the genre. Basing his screenplay on the novel by Thomas Pynchon, Anderson has stated that the narrative is deliberately confusing, which can get a little wearying when stretched out over two-and-a-half hours.

Luckily, the fantastic production design, costumes, tunes, and wild performances might just be enough to tide you over if you give up trying to follow the story. Phoenix displays some surprising comic chops in an occasionally madcap role, especially when paired with Josh Brolin as a hard-nosed, super-square detective. They’re both a hoot, and Martin Short also makes a hilarious cameo as a coke-snorting dentist.

Inherent Vice is more of a vibe than a movie, but unlike its close cousins The Long Goodbye (1973) and The Big Lebowski, seems a little sadistic in its reluctance to let the viewer get anywhere close to keeping track of what’s going on. I like stoner comedies and LA-based detective noir for it to just about warrant repeat viewings, but I can also see how it would annoy the hell out of some people. Overall, this is the Anderson movie that amounts to least.

Phantom Thread (2017)

For his final role before retirement, Daniel Day-Lewis gave one of his most fascinating performances in Phantom Thread. Naturally, the meticulous method man spent a year learning how to make dresses for the role of Reynolds Woodcock, a celebrated haute couture fashion designer in ‘50s London.

We’re never told what his problem is, whether he’s somewhere on the spectrum or simply a very strange man. Reynolds is obsessive about his daily routine, a perfectionist in his work, and harsh on anyone else who fails to meet his exacting standards. That goes for his lovers, too; once he loses interest in them, he leaves it up to his stern sister, Cyril, to usher them out of his life.

Things change when he meets Alma, a young waitress who at first seems a little naive. They start a relationship and, when it comes for the time when she displeases him and Reynolds wants her to go away, Alma’s having none of it and hatches a very dangerous plan to keep their relationship alive.

As with There Will Be Blood and The Master, Phantom Thread is a riveting study of the power dynamic between two very idiosyncratic, forceful people. Having the clash between a man and a woman this time around gives the film another dimension, minutely detailing the power plays and micro-aggressions of their relationship, making it one of the strangest, darkest romantic comedies around.

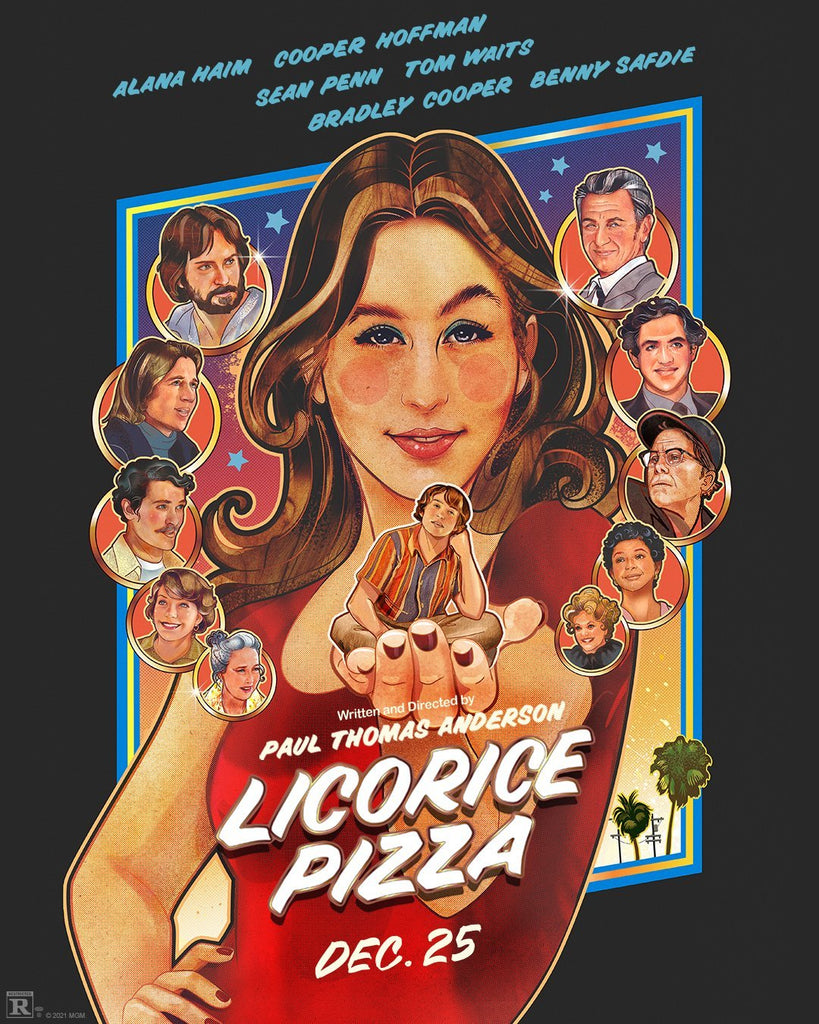

Licorice Pizza (2021)

Paul Thomas Anderson has often written strong parts for women, such as Julianne Moore in Boogie Nights and Amy Adams in The Master, but they are usually supporting roles. He finally made up for that in Licorice Pizza, his charming, rambling, nostalgic rom-com that follows the on-off relationship between Alana (Alana Haim), a grumpy photographer in her mid-twenties, and 15-year-old Gary (Cooper Hoffman), a self-confident schoolboy entrepreneur.

The film was Haim’s feature film debut and she is an absolute revelation in the role. Anderson wrote the part with her in mind because he is friends with her family and directed several music videos for Haim, the pop trio consisting of Alana and her two older sisters.

With her snarky attitude and plain features, she’s an unusually prickly leading character, challenging the viewer to see past her innate shittiness to the good heart within. She’s almost matched by Hoffman, the late Philip Seymour’s son, and together they make a wonderful odd couple.

From Boogie Nights onwards, Anderson had the luxury of casting well-established, extremely talented actors in his ensembles. Licorice Pizza is the first film where his casting lets him down. Relative unknowns Haim and Hoffman are absolutely incredible, giving the most naturalistic performances in his entire filmography, but they are deserted by Anderson stacking the latter half of the film with big showy cameos from Bradley Cooper, Sean Penn, and Tom Waits.

They are all super entertaining, but their star presence almost capsizes the movie. The usually dour Penn, playing an uncharacteristically zany part, almost broke the movie for me. Luckily, I was already so invested in Haim and Cooper’s guileless performances that I managed to get past the shameless showboating to the heart-warming, heartfelt ending.

So there you have it, our rundown of Paul Thomas Anderson’s career to date. Are you a fan, or do you think he’s overrated? What are your picks of his films? Let us know!