When I was a kid, it seemed like Technicolor must be some kind of enchanted potion that bubbles out of the ground somewhere in the Hollywood Hills. I know better than that now, of course, but it still has the same effect on me. Very few things say “movie magic” more than the dazzling brilliance of Technicolor, brighter than life and capable of banishing the worries of the ordinary world for a few hours.

We may instantly be able to recall what Technicolor looks and feels like, but what exactly is it? Colour pictures date back as far as A Trip to the Moon 1902 when George Melies hand-coloured the film, and subsequent early efforts were similarly primitive. Technicolor, founded in 1914, developed the concept further by exposing two strips of black-and-white film to red and green filters and merging the two to create a rudimentary colour image.

The technology continued to evolve until 1932 when a third colour, blue, was also added to the process. This created three-strip films and gave birth to the rich saturated tones that we think of when we hear the word Technicolor.

Walt Disney was an early advocate, shooting one of his Silly Symphonies cartoons in three-strip before fully embracing Technicolor in later masterpieces like Snow White and The Seven Dwarves. As the process entered its heyday in the late ‘30s, it became synonymous with the lavish production value of Hollywood golden oldies. It also had greater artistic possibilities, too. In the hands of a great director and cinematographer, it could be used in an expressionistic way to convey emotions, themes, motifs, and the psychological state of characters.

There are many brilliant examples of Technicolor films, but here are my picks.

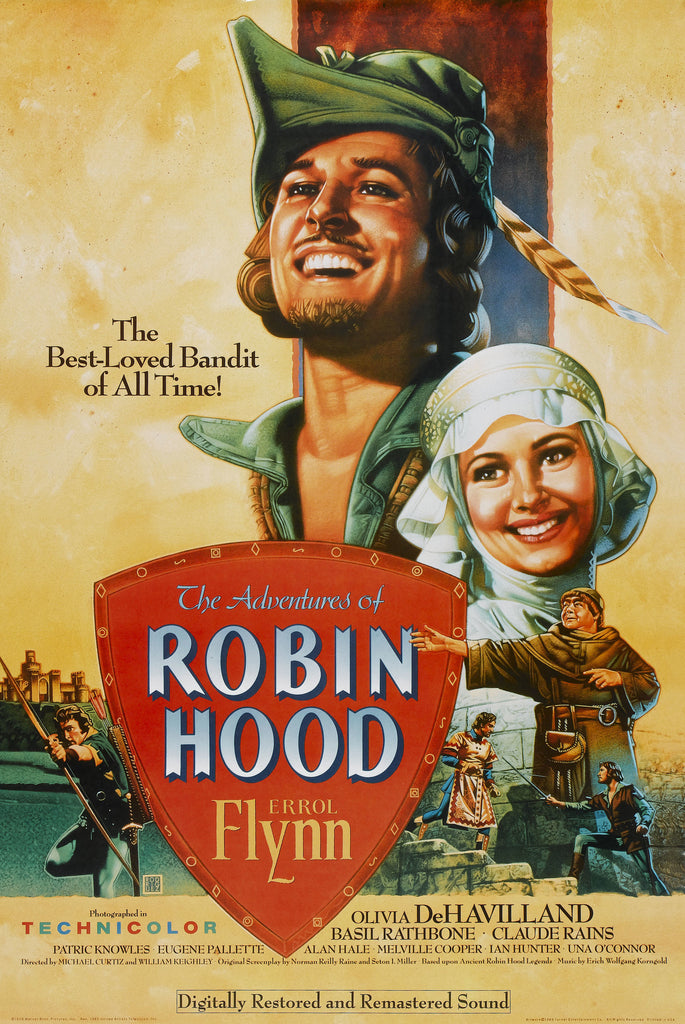

The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

Now over 80 years old, The Adventures of Robin Hood is still the definitive screen version of the oft-told tale, packing in as much charm, adventure, comedy, romance, and swashbuckling as all the others combined. Key to its longevity is the wonderful central performance from Errol Flynn. It might be easy to poke fun at his cap and Lincoln green tights (as Mel Brooks did in Robin Hood: Men in Tights) but Flynn simply is Robin Hood, effortlessly embodying the character’s breezy heroism and swaggering good spirits. It’s a fine physical performance: Flynn was a strapping fellow, but he moved as if gravity didn’t have the same burdening effect on him as it does for everyone else.

The rest of the cast are great, too. Olivia de Havilland is suitably radiant as Maid Marian and the hissable duo of Claude Rains and Basil Rathbone as Prince John and Guy of Gisburne make memorable screen villains.

Then you have the glorious Technicolor, which isn’t as gaudy as you might expect considering the costumes. There is a beautiful feathery quality to it that makes each frame look like it comes from an old book of fairytales. With its irrepressible brio, it’s a film that really puts the “Merry” into “Robin Hood and His Merry Men.” Watching it will make you add planting both hands on your hips and throwing your head back in raucous laughter to your social repertoire.

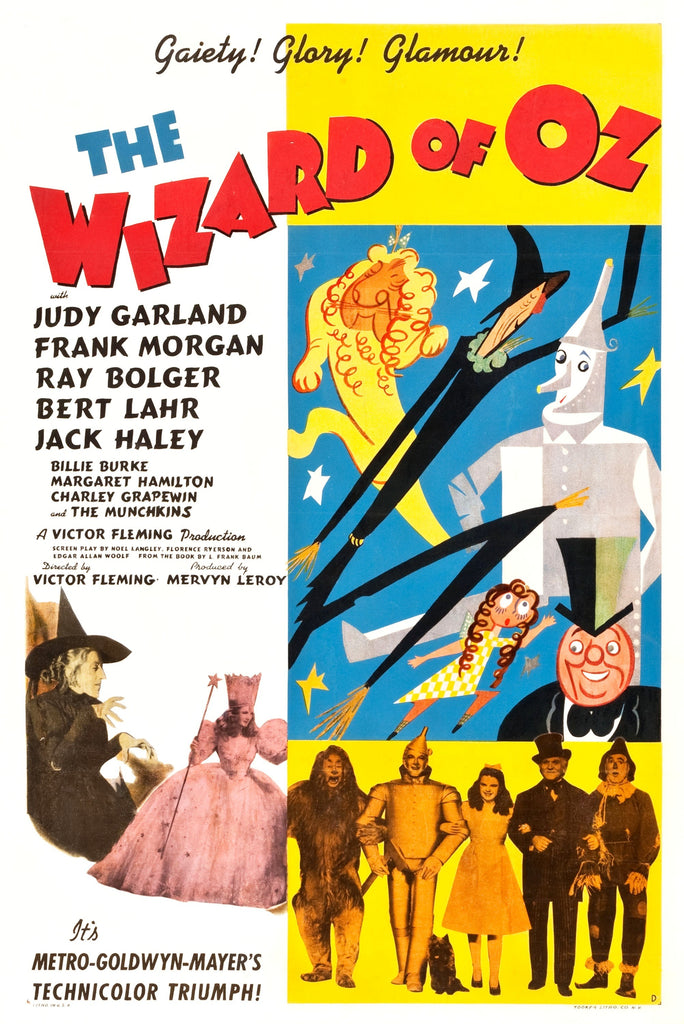

The Wizard of Oz (1939)

Like It’s a Wonderful Life, Victor Fleming’s eye-popping adaptation of L. Frank Baum’s timeless novel became a staple of festive TV schedules, and over-familiarity has perhaps dulled the original sense of wonderment. That’s what I thought, anyway, until a recent viewing with the kids revealed that all the old magic is still present and correct.

Reportedly hell to make and hazardous for the cast and crew, all the hard work came together on the screen to become one of the most enduringly popular Technicolor classics. Following dauntless Dorothy (Judy Garland) and Toto on their adventures in Oz, the performances are still captivating and the tunes relentlessly ear-wormy. Like Frank Capra’s Christmas classic, the iconic moments have entered our collective pop consciousness, but it is the visuals that still dazzle to this day.

The decision to bookend Dorothy’s journey to the Emerald City with sepia-toned black-and-white scenes at home in Kansas is what really sells it. The moment when she opens the door to reveal the Technicolor land of Oz beyond is one of the most breath-taking transitions in cinema history.

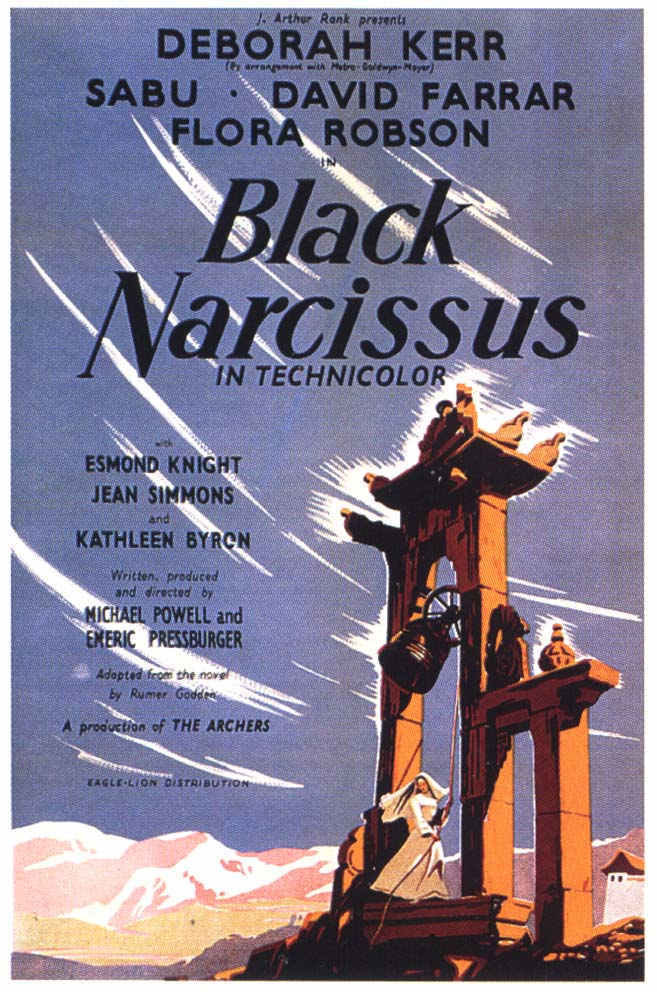

Black Narcissus (1947)

While Technicolor is often associated with Hollywood movies, there is a strong case that British filmmaking duo Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger were the true masters of the medium.

As the writer-producer-director team known as The Archers, they started out in black-and-white before transitioning to Technicolor for a string of masterpieces including The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes, and my pick, Black Narcissus.

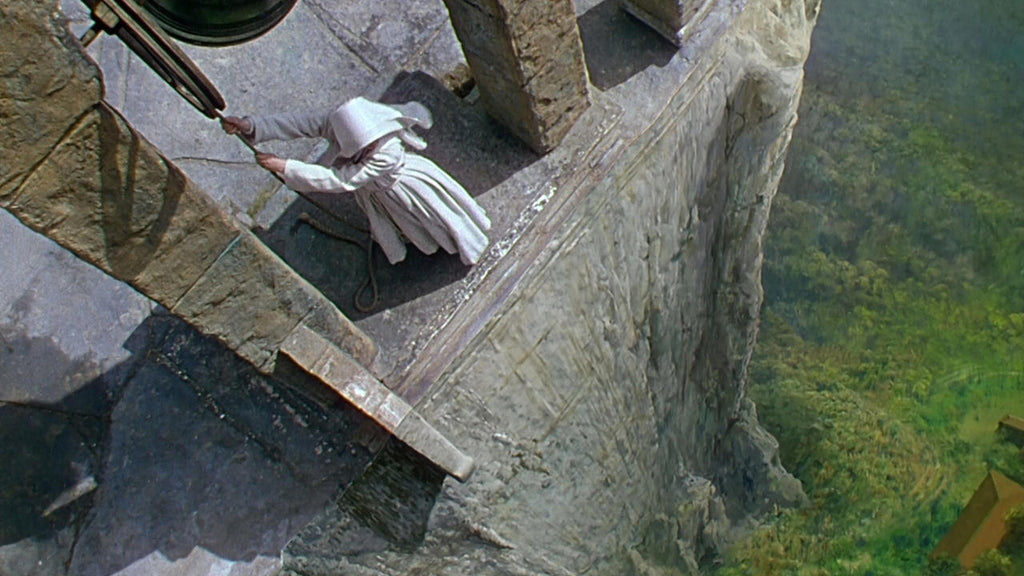

Focusing on a group of nuns who set up a missionary in an ancient windswept palace high in the Himalayas, Sister Ruth (Kathleen Byron) becomes murderously unhinged when she sees Sister Clodagh (Deborah Kerr) as her love rival.

Regular Archers cinematographer Jack Cardiff and production designer Alfred Junge deserve much of the credit for conjuring up an atmosphere of lush exoticism, using stunning matte paintings to believably turn Pinewood Studios into the nuns’ vertiginous perch high in the mountains. It’s little wonder that the Sisters begin to feel a little giddy under the wimple as the film builds to a proto psycho-thriller crescendo. As Sister Ruth stalks Sister Clodagh with homicidal intent, the frame becomes saturated with red, reflecting her burning psychological state.

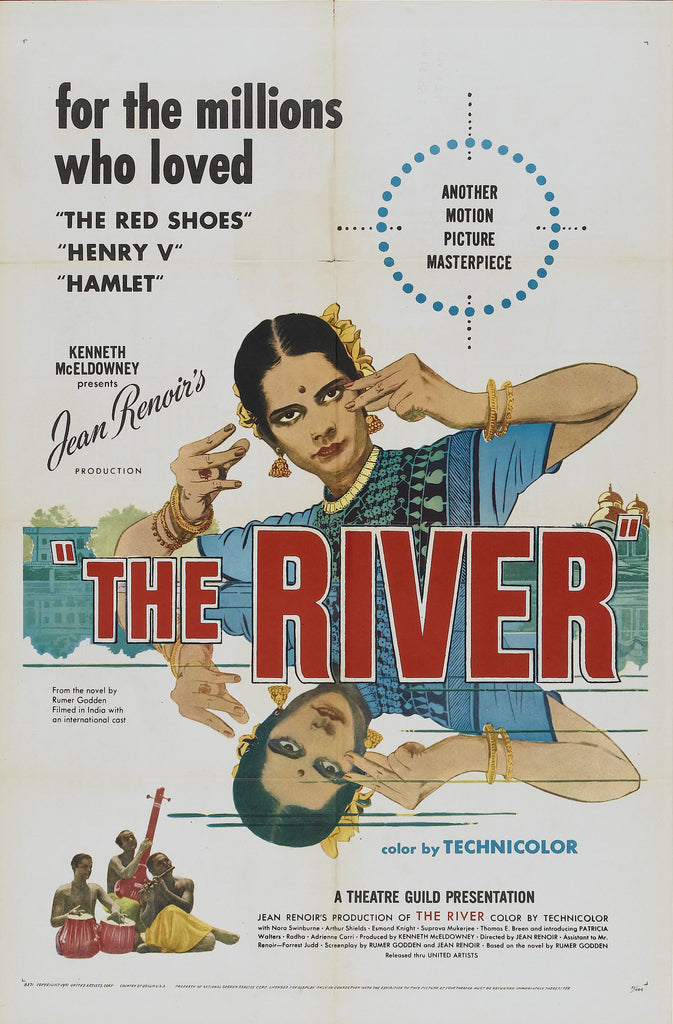

The River (1951)

After staking his claim to cinematic greatness in his home country with films like La Grande Illusion and The Rules of the Game and a successful spell in Hollywood, French director Jean Renoir embarked on a new adventure. The River was his first film in colour, part travelogue and part coming-of-age tale shot on location in newly independent India.

Based on the book by British author Rumer Godden, who grew up in India and used it as the backdrop for her most famous works (also including Black Narcissus), The River is a rich snapshot of the subcontinent at a new phase of its history. The ebbs and flows of the film’s insights run parallel to the fortunes of a British family living on the banks of the Ganges, in particular Harriet (Patricia Walters), a young woman making the tricky transition from adolescence to adulthood and encountering first love along the way.

Unlike many of the other films on this list, the Technicolor in The River is used more subtly and naturalistically to capture the vibrant culture Renoir observes, culminating in a truly astonishing Hindu dance sequence. Martin Scorsese has named it and Powell and Pressburger’s The Red Shoes as the two most beautiful films ever shot in colour. Who is going to disagree with him on this evidence?

Singin’ in the Rain (1952)

I’ve often said that if there is a purer expression of cinematic joy than Singin’ in the Rain, I’ve yet to see it. Some may say that Vincent Minnelli used Technicolor to greater artistic expression in An American in Paris the previous year, but for me, Singin’ in the Rain is the Technicolor musical by which all others are measured. I’ll even go one further and say it is the film that springs to mind when I think about Technicolor in general.

Cinematographer Harold Rossen (who also shot The Wizard of Oz) tunes his palette in such a way that it perfectly matches the chipper bonhomie of Gene Kelly, Debbie Reynolds, and Donald O’Connor. The wonders of Technicolor are given full range, from the inconsequential showreel of “Beautiful Girl" to the elegant pastel dreaminess of “You Were Meant For Me” and the ravishing “Broadway Melody.” That’s before you even get to the more well-known showstoppers like the title tune and O’Connor’s breathless “Make ‘Em Laugh".

(Credit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer)

Singin’ in the Rain is one of my favourite films. Not only is it the greatest Hollywood musical ever made, it is also a fine comedy too, a surprisingly sharp satire on the painful transition from cinema’s silent era to the talkies. It’s one of those movies that always makes me feel better no matter what my mood. If I’m a little glum, it cheers me up. If I’m already pretty cheerful, it will make me feel ecstatic.

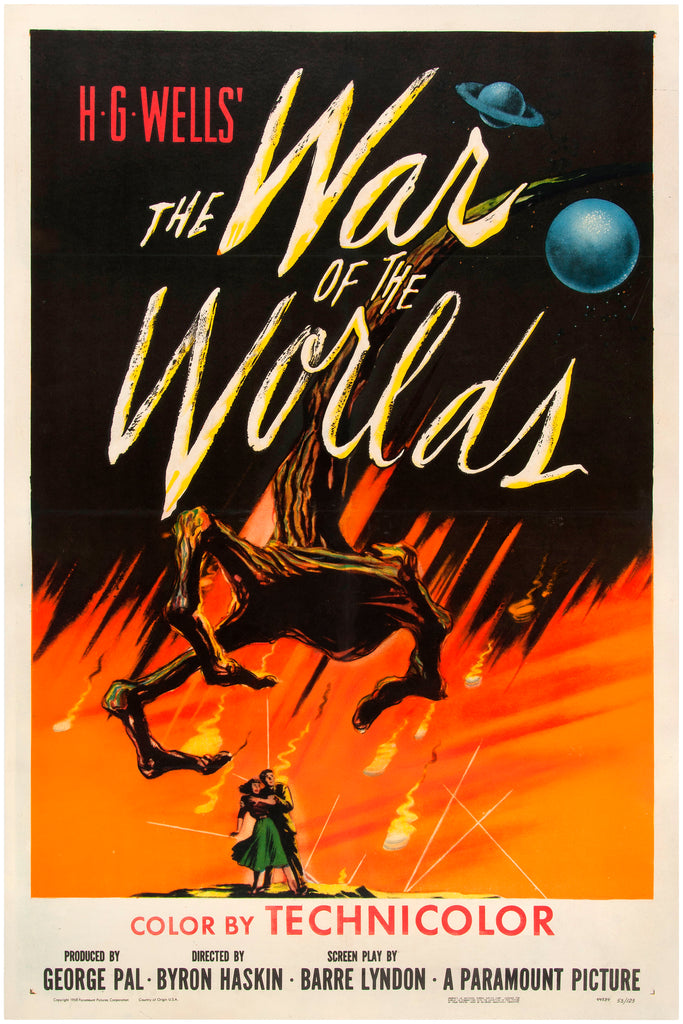

The War of the Worlds (1953)

Tales of alien visitors were ten-a-penny in ‘50s science fiction, but The War of the Worlds stands out among esteemed contemporaries like The Day The Earth Stood Still and The Thing From Another World with its shattering use of Technicolor.

I loved these old sci-fi flicks when I was a kid, and there is one moment from this movie that particularly burned itself into my brain. It’s the scene when a small town vicar bravely marches out to meet the martian invaders with his bible in hand. A sleek flying war machine rises up in front of him, one menacing red eye glowing at the end of its slender metallic neck, and blasts him to ashes.

Like many Atom Era classics, there are large tracts of The War of the Worlds that really drag with dry dialogue between stock characters, but when it gets going it is still incredibly intense. A large part of this is down to how Oscar-winning cinematographer George Barnes shoots the marauding martian ships, clashing hellish reds with sinister greens as they float serenely across the Californian landscape laying waste to everything before them. It’s a great example of how colours from opposite sides of the colour wheel can be used to disturbing effect, and it is especially powerful in vivid Technicolor.

All That Heaven Allows (1955)

German-born Douglas Sirk was one of the most unconventional and subversive directors working in Hollywood, hitting his creative peak with a string of Technicolor masterpieces that masked satire and social critique with soapy melodrama. He trod a fine line between taking the piss and genuine sincerity, but the core message of films like Written on the Wind, Magnificent Obsession and Imitation of Life was always bold, potent, and ahead of its time.

All That Heaven Allows is Sirk’s greatest film, both his most accessible and keenly heartfelt, a tear-jerking story about a middle-aged widow Cary (Jane Wyman) who falls for her younger gardener Ron (Rock Hudson), causing plenty of pearl-clutching in her small town community and the disapproval of her spoilt kids.

The photography is sumptuous, heightening the melodramatics with a kitschy chocolate box quality. Yet although it looks like pure unadulterated Americana, the central romance is still very moving, and Technicolor is used to its fullest in scenes by Ron’s picture window, which changes hue to match the couple’s emotions.

The film proved influential, inspiring both Rainer Werner Fassbender’s brilliant Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and John Waters’ Polyester.

The Red Balloon (1956)

This enchanting short film is kind of like a French Kes, if Kes was a balloon instead of a bird and with Parisian whimsy in place of Ken Loach’s bleak social realism. It’s a simple story of boy meets balloon, balloon follows boy around, bullies pop balloon, balloon’s mates take boy on a magical flight across the city. It was a labour of love for Albert Lamorisse who wrote, produced, and directed the film, and also cast his son Pascal in the lead role. He certainly commits to the central premise, managing to convince us that the balloon is somehow sentient and building a rapport with the kid.

Technicolor is used to great effect to contrast the bright primary colours of the balloons with the greyness of the city streets, and the boxy 4:3 aspect ratio combined with the balloon’s tendency to drift skywards gives the film an unusual verticality. Often regarded as a children’s film, there is plenty of wonder in The Red Balloon for anyone to enjoy, and it received multiple international awards, including the Oscar for Best Original Screenplay and the Palme d’Or for short films at Cannes.

(Credit: Lopert Pictures)

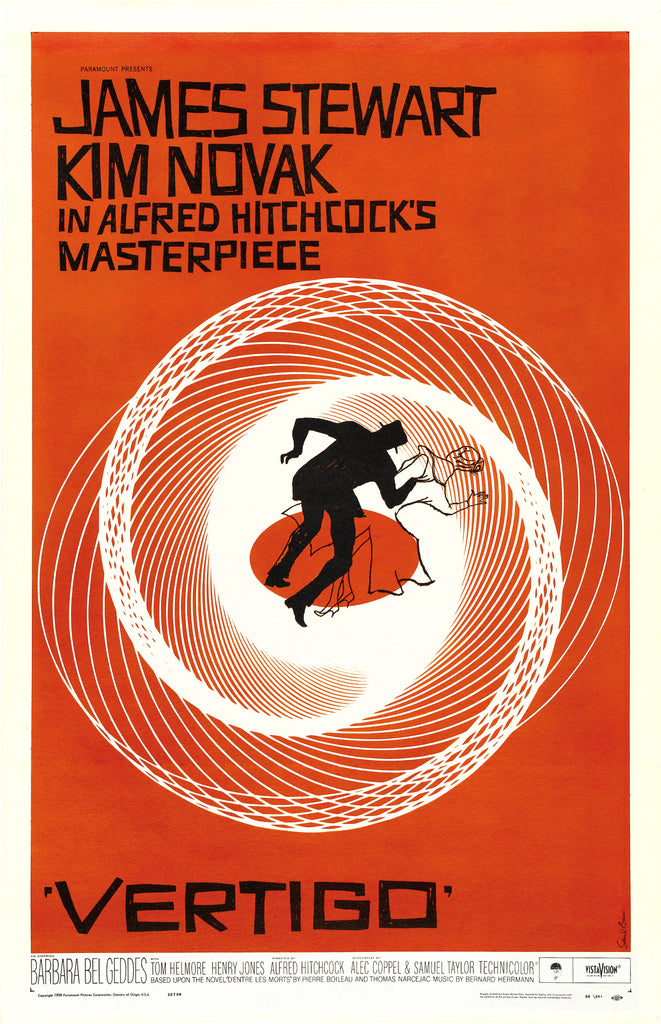

Vertigo (1958)

In a career spanning over 50 years, Alfred Hitchcock’s peak Hollywood run during the ‘50s fully embraced Technicolor. This period included classics like Dial M For Murder, Rear Window, and North By Northwest, but there is a somewhat garish quality to them that prompted Orson Welles to slag the Master of Suspense for making films that were “all lit like television shows.” He also took down Vertigo, claiming it was “even worse than Rear Window,” but the mercurial Mr. Welles was totally wrong on that one.

James Stewart played his darkest role as Scottie Ferguson, a San Francisco detective who takes a private gig following Judy (Kim Novak), an old friend's wife who seems to believe she is the reincarnation of a historical figure before apparently committing suicide. As the story progresses, his kinks become twisted obsessions as he moulds a shop girl Madeleine (also Kim Novak) into the image of the deceased.

There is a depth and shimmer to the Technicolor in Vertigo that almost seems to render the images three dimensional, from the celestial sheen of Kim Novak’s platinum blonde hair to the mysterious Redwood forest where our troubled protagonist tracks his target to.

The colour green is prominent throughout, tying in with the key theme of Scottie’s envy and possessiveness and closely associated with Judy/Madeleine, the object of his lust and controlling nature. This all culminates in the famous scene when she Madeleine “becomes” Judy for him in a hotel room bathed in green neon light, wearing the same clothes and changing her hair colour to satisfy Scottie’s fetish.

Hitchcock’s thing for icy blondes was well documented and Vertigo can be seen as his most personal film, laying all his own kinks out on the screen for the audience. As with Black Narcissus, it’s a thrilling example of how Technicolor can be used so effectively to put us in a character’s headspace.

Suspiria (1977)

Named after the yellow (giallo) covers of cheap Italian pulp novels and daubed liberally with garish blood, Giallo horror movies are by definition colourful. Dario Argento, one of the key figures of the genre, reached the peak of his artistic expression in perhaps his best known film, Suspiria, often regarded as the last great Technicolor film.

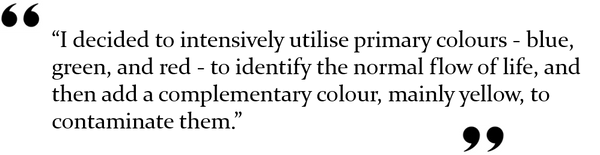

Following a young dancer who has the misfortune to attend a ballet school in the German Black Forest run by a coven of witches, Argento and cinematographer Luciano Tovoli use a bold palette of primary colours and deep blacks, combining with the intense set design and Goblin’s evocative score to create a truly phantasmagorical atmosphere. Tovoli said:

The effect doesn’t just heighten reality, it fractures it, giving us the sense that Jessica Harper’s protagonist has entered a dark fairytale world from the moment she steps off the plane at Munich airport. As scary as the film is, few horror movies before or since have looked so beautiful. You can see traces of Suspiria’s influence in the retro visual style of SpectreVision’s Mandy and Color Out of Space.

(Credit: Seda Spettacoli/Produzioni Atlas Consorziate)

So there you have it, some of my favourite Technicolor movies. The list is far from definitive, so what are your picks? Let us know!